You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

One must only open an anatomy text to understand the proximity of the dentition to the maxillary sinus cavities. In 40% of patients, the first and second maxillary molar roots possess an intimate association with the antral floor, through which they pierce in 2.2% and 2% of cases, respectively.1 Those patients who have experienced a case of acute sinusitis are undoubtedly aware of this intimate relationship based on the experience of pain and discomfort in both structures. Traditionally, the management of sinusitis has focused on its common origins within the respiratory tract, namely those of viral, bacterial, or allergic causes, compounded by certain predispositions posed by anatomic variants among patients.2 The past decade has seen a body of literature emerge showcasing the frequency of odontogenic causes of sinusitis.

In fact, maxillary sinusitis caused by dental pathology is common, particularly unilateral sinusitis. According to one recent publication, approximately 34% to 50% of all maxillary sinusitis cases are of odontogenic origin.3 In a study by Maillet et al, 70 out of 135 sinusitis cases identified on cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) imaging were of odontogenic cause, resulting in a 51.8% incidence of odontogenic sinusitis.4 In addition, up to 75% of unilateral maxillary sinusitis cases resulted from an odontogenic pathology.3 These findings underscore the need for physicians to consider an odontogenic etiology of sinus disease, particularly unilateral sinus disease, and for the inclusion of dental practitioners in multidisciplinary teams in the management of sinusitis cases.

Interrelated Sinus and Dental Pathology

The proliferation of dental technology, particularly the advent of CBCT imaging, has advanced clinicians' understanding of interrelated sinus and dental pathology. Classically, dentists understood that sinus pain could refer to the dentition and vice versa but rarely considered overlap between the two conditions. Two-dimensional (2D) imaging in particular was limited in its ability to assess for radiologic presentations of both disease processes. With the incorporation of CBCT imaging into dental practice, however, the complex interrelationship between the two entities becomes clearer and cannot be ignored. In fact, odontogenic disease can manifest with symptomatic or asymptomatic inflammation of the adjacent sinus tissues. Periodontal disease and endodontic disease are associated with the formation of sinus findings, namely mucositis.5

When sinusitis develops secondary to endodontic disease, the term "maxillary sinusitis of endodontic origin" (MSEO) has been proposed as the best descriptor of this unique form of sinus disease.6 In cases of MSEO, periapical inflammation often results in radiographic changes in the maxillary sinus. These presentations may include periapical mucositis and periapical osteoperiostitis. Periapical mucositis, wherein the soft tissue of the sinus floor may expand with localized mucosal tissue edema, appears as a relative radiopacity within the sinus lining. In periapical osteoperiostitis, the bony sinus floor is displaced upward into the sinus with additional layers of bone being deposited on the inner periphery. Both radiographic presentations can progress if not treated.6

Ultimately, suspicion of odontogenic causes of sinus disease should come as a relief for both the provider and patient as the conditions are very treatable by noninvasive means with an excellent prognosis. The diagnosis of MSEO requires a thorough medical and dental history. It can present with varying dental and sinonasal symptoms, including congestion, rhinorrhea, retrorhinorrhea, facial pain, and foul odor.7 However, odontogenic sinusitis may also be asymptomatic. Between 1% and 47% of cases have no dental or sinus symptoms reported.7 Regardless of whether dental symptoms present in these cases, an odontogenic etiology must still be considered for any sinus disease, particularly when unilateral. Physicians, especially otolaryngologists, should work closely with dental practitioners in the management of odontogenic sinusitis, because dental rather than medical or pharmacologic interventions are required for its resolution. Given the complexity of diagnosis and the utility of incorporating advanced technologies like CBCT imaging, endodontic specialty referral is often warranted.

Thorough Evaluation

A comprehensive endodontic evaluation is indicated for any patient with suspected MSEO.6 The practitioner must perform examinations of the hard and soft tissues, including a limited periodontal examination. Examination must also entail pulp sensitivity testing, including the use of thermal and electric pulp tests when relevant, and tests for periapical symptoms, including percussion, palpation, and biting.6 From these tests, in cases of MSEO, the tooth in question may demonstrate signs of an inflamed or necrotic pulp, further pointing to an odontogenic source of infection and, therefore, the need for endodontic therapy.6

Using CBCT as opposed to 2D imaging, practitioners are much more likely to capture periapical findings of MSEO. Pathology may not appear in conventional 2D imaging, as periapical radiographs do not adequately observe the relationship between maxillary molar roots and the sinus floor.3 CBCT scans have higher spatial resolution than 2D scans, as well as a lower radiation dose, faster imaging capabilities, and lower cost compared to classic CT.3 According to Low et al, CBCT scans revealed 34% more lesions than periapical radiographs in maxillary posterior teeth.8 With the use of CBCT scans, MSEO can present with periapical lesions and sinus floor mucosal changes, particularly unilaterally. CBCT scans are extremely useful in highlighting pathological changes in the maxillary sinus, including bone destruction, inflammation in lower mucosa, and sinus opacification.3 Therefore, with its resolution and accuracy, CBCT has demonstrated to be an indispensable diagnostic tool and has consistently shown itself to be the optimal tool for making a reliable diagnosis of MSEO.3

Treatment of MSEO

The primary treatment of MSEO must address the odontogenic etiology of the sinus disease, namely the periapical pathology. Nonsurgical root canal therapy (NSRCT) may be performed to remove the pathogenic microorganisms harboring in the pulp of the tooth that caused the periradicular pathology.6 In cases of recurrent or persistent endodontic pathology, nonsurgical retreatment represents a reasonable treatment option.6 Periradicular surgery may be contraindicated, however, due to the risk of an iatrogenic oroantral fistula resulting from the close proximity between the apices of the maxillary teeth and the sinus floor.6 For initial or recurrent endodontic pathology, extraction of the infected tooth may be suggested when the tooth is deemed to be unrestorable but does not pose a high risk of creating an iatrogenic oroantral fistula.6 The prognosis for these treatment modalities is excellent with appropriate case selection.6

While treatment of the odontogenic source of MSEO is frequently sufficient to resolve the sinus pathology, some cases will require concurrent medical management. Cases of persistent sinonasal symptoms, for example, may prompt the otolaryngologist to supplement treatment with additional pharmacologic or surgical interventions. Pharmacologic therapies may include isotonic nasal saline irrigation, topical intranasal corticosteroids, antibiotics, and oral corticosteroids, as indicated in treating chronic rhinosinusitis.9 While antibiotics may be considered in accordance with an antibiogram,10 one study showed that 79% of cases did not respond to antibiotic treatment, thus indicating the need for surgical interventions.11 Surgical interventions may involve functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS), which is the gold standard for treating chronic rhinosinusitis.12 The targeted outcomes from providing FESS in treating sinusitis are to "enlarge sinus ostia, restore adequate aeration of sinuses, improve mucociliary transport, and provide a better route for topical therapies."11

In a study conducted by Wang et al, 33% of the patients in the participating cohort required concurrent sinus surgery with dental surgery for complete disease resolution.13 In another retrospective review, 52% of the patients with odontogenic sinusitis improved with medical and dental treatment, while 48% required endoscopic sinus surgery.14 Thus, to fully and extensively manage treatment of MSEO, it is critical for physicians and dental practitioners to work together as a multidisciplinary team.

Case Presentations

The following two case presentations demonstrate thediagnosis and management of MSEO and the benefits CBCT imaging can provide in such cases.

Case 1

A 62-year-old female patient presented to the endodontist on referral from her general dentist to evaluate tooth No. 13 with visible radiographic pathology. She denied dental pain, but reported long-standing symptomatic sinusitis of unknown origin that was not responsive to over-the-counter treatments, including nasal sprays and decongestants. Clinical examination found that tooth No. 13 was unresponsive to pulp sensitivity tests and non-tender to percussion and palpation. A full-coverage ceramic crown was intact, and adjacent soft tissues were unremarkable.

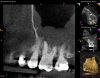

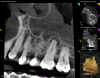

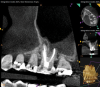

Periapical and CBCT imaging confirmed the presence of apical pathology, as well as a dramatic sinus communication with MSEO (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The diagnosis for tooth No. 13 was pulpal necrosis with asymptomatic apical periodontitis. NSRCT was completed (Figure 3). At the patient's 1-year follow-up appointment, tooth No. 13 remained asymptomatic, her sinusitis was resolved, and complete radiographic healing of both periapical pathology and the MSEO was noted (Figure 4).

Case 2

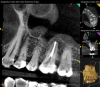

A 52-year-old male patient was seen by his otolaryngologist for symptomatic and unilateral sinusitis of 6 months duration. Medical CT showed dental pathology (Figure 5). His general dentist had a bitewing radiograph on file and referred the patient for endodontic evaluation (Figure 6).

As part of the endodontic evaluation, CBCT imaging showed periapical pathology associated with tooth No. 14 as well as significant MSEO (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Clinical testing confirmed the absence of a cold response but no tenderness to percussion or palpation. A composite buildup was in place, absent evidence of recurrent decay. Soft tissues were unremarkable.

The diagnosis for tooth No. 14 was pulpal necrosis with asymptomatic apical periodontitis. NSRCT was completed (Figure 9), followed by full-coverage restorative care performed by the general dentist. A 3-month follow-up revealed resolution of prior sinus symptoms, normal clinical findings, and healing radiographic pathology, including periapical pathology and associated maxillary sinus mucositis (Figure 10 and Figure 11).

Discussion

Both of these cases illustrate the improvement in sinus pathology findings from preoperative CBCT scans to postoperative recall CBCT scans following NSRCT (Figure 4, Figure 10, and Figure 11). In addition, in both instances the re-establishment of the previously obliterated cortical boundary between the apex and maxillary sinus was impressive. Clinically, the resolution of sinusitis symptoms in both patients after receiving nonsurgical endodontic therapy was quite notable. Despite the absence of specific dental pain, these patients' sinusitis symptoms could not have been alleviated without the endodontic interventions due to the odontogenic etiology of their disease. These two cases demonstrate the pivotal role of CBCT imaging in diagnosis and recall as well as the success of NSRCT when treating cases of MSEO.

Conclusion

MSEO is a common diagnosis that can be readily managed when treated appropriately. Many patients suffer from sinusitis symptoms for prolonged periods when the etiology of infection goes unaddressed. It is evident that this etiology is often a dental infection, especially in cases of unilateral sinusitis. Collaboration between dental practitioners and otolaryngologists is essential in the management of odontogenic sinusitis, beginning with diagnosis. CBCT 3D imaging represents the most useful tool in the diagnosis of MSEO, and dental practitioners who are managing referrals from medical parties should prioritize its usage.

While there are many treatment modalities for MSEO, both NSRCT and nonsurgical retreatment are proven conservative treatment options with a high success of maintaining the teeth in question. Through these nonsurgical treatment modalities, as well as additional surgical or pharmacological sinus treatments if necessary, patients can be relieved of their sinusitis symptoms in conjunction with removal of the source of odontogenic infection. By keeping patient well-being at the core of practice, dental practitioners and otolaryngologists can provide interdisciplinary care to successfully manage cases of MSEO.

About the Authors

Jenna Zhu, DMD

Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts

Brooke Blicher, DMD, Certificate in Endodontics

Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Endodontics, Tufts University

School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; Lecturer, Department of Restorative Dentistry and Biomaterials Science, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston,Massachusetts; Private Practice limited to Endodontics,

White River Junction, Vermont

Rebekah Lucier Pryles, DMD, Certificate in Endodontics

Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Endodontics, Tufts University

School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; Lecturer, Department of Restorative Dentistry and Biomaterials Science, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston,Massachusetts; Private Practice limited to Endodontics,

White River Junction, Vermont

Queries to the author regarding this course may be submitted to authorqueries@broadcastmed.com.

References

1. Somayaji K, Muliya VS, KG MR, et al. A literature review of the maxillary sinus with special emphasis on its anatomy and odontogenic diseases associated with it. Egypt J Otolaryngol. 2023;39:173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-023-00536-7.

2. Langella J, Blicher B, Lucier Pryles R. Maxillary sinusitis of endodontic origin. Inside Dentistry. 2019;15(1):35-39.

3. Zhang J, Liu L, Yang J, et al. Diagnosis of odontogenic maxillary sinusitis by cone-beam computed tomography: a critical review. J Endod. 2023:S0099-2399(23)00536-8.

4. Maillet M, Bowles WR, McClanahan SL, et al. Cone-beam computed tomography evaluation of maxillary sinusitis. J Endod. 2011;37(6):753-757.

5. de Lima CO, Devito KL, Baraky Vasconcelos LR, et al. Correlation between endodontic infection and periodontal disease and their association with chronic sinusitis: a clinical-tomographic study. J Endod. 2017;43(12):1978-1983.

6. American Association of Endodontists. Maxillary Sinusitis of Endodontic Origin. AAE Position Statement. 2018. https://www.aae.org/specialty/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/04/AAE_PositionStatement_MaxillarySinusitis.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2024.

7. Craig JR. Odontogenic sinusitis: a state-of-the-art review. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;8(1):8-15.

8. Low KM, Dula K, Bürgin W, von Arx T. Comparison of periapical radiography and limited cone-beam tomography in posterior maxillary teeth referred for apical surgery. J Endod. 2008;34(5):557-562.

9. Sedaghat AR. Chronic rhinosinusitis. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(8):500-506.

10. Martu C, Martu MA, Maftei GA, et al. Odontogenic sinusitis: from diagnosis to treatment possibilities - a narrative review of recent data. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(7):1600.

11. Yokubovich SI, Sharipovna IF, Jurakulova HN. New approaches in the treatment of odontogenic sinusitis. Cent Asian J Med Nat Sci. 2021;14:57-60.

12. Homsi MT, Gaffey MM. Sinus endoscopic surgery. 2022 Sep 12. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563202/. Accessed April 24, 2024.

13. Wang KL, Nichols BG, Poetker DM, Loehrl TA. Odontogenic sinusitis: a case series studying diagnosis and management. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(7):597-601.

14. Mattos JL, Ferguson BJ, Lee S. Predictive factors in patients undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery for odontogenic sinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6(7):697-700.