You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

The American Association of Endodontists defines a flare-up as "an acute exacerbation of an asymptomatic pulpal and/or periradicular pathosis after the initiation or continuation of root canal treatment." Walton and Fouad characterized flare-ups clinically as presenting with severe pain and/or swelling several hours to days after a root canal procedure that is intense enough to cause an unscheduled visit back to the dentist.1 Without clear disease features apparent on examination or imaging, except for swelling in a subset of patients, the diagnosis of an endodontic flare-up is primarily clinical, guided by the patient's history of symptoms and treatment timeline. If, however, the pain symptoms persist despite active treatment of the endodontic flare-up, the clinician should consider other etiologies, including fracture, missed canals, delayed healing due to systemic disease, temporomandibular disorder, and trigeminal neuralgia.2

A meta-analysis by Tsesis et al reported an average flare-up incidence of 8.4%, although some studies have reported rates as low as 0.39% and as high as 50%.3-5 The wide range in incidence can be explained by several study factors, including varying treatment modalities, levels of provider experience, and inclusion criteria given the absence of a universally utilized disease definition. For instance, the incidence rate of 0.39%, reported by Iqbal et al,4 included patients necessitating an emergency visit and active treatment after nonsurgical root canal therapy (NSRCT) completed by graduate endodontic residents operating under the supervision of trained endodontic specialists, while an incidence rate of 18.3% reported by Oginni et al involved less-stringent study criteria of any post-NSRCT pain uncontrolled by over-the-counter medication regardless of whether an emergency visit was made and included patients treated by general dentists.6 It has been suggested that a strict definition of flare-up that involves severe pain or swelling leading to an unscheduled visit and active treatment may help distinguish patients experiencing a true flare-up from those experiencing expected postoperative pain.4,6

Etiology

The etiology of endodontic flare-ups lies in a dynamic interplay between chemical, mechanical, and microbial factors. While mild discomfort is not unusual following endodontic therapy, flare-up symptoms can be exacerbated by overinstrumentation, an altered microbial and host defense environment, and irritation of the periapical tissues from extrusion of cytotoxic irrigants, medications, and filling materials.7-9 Determining the specific mechanism driving a flare-up is exceedingly challenging, and further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying pathophysiology.

Siqueira suggested that microbial factors are a key driver of flare-ups, describing a disruption in the balance between host immune defenses and microbial aggression that results in acute periradicular inflammation. The quantity and virulence of microorganisms in the periradicular tissue are thought to contribute to the intensity of the inflammatory reaction.9

Two mechanisms have been proposed for the aforementioned shift in microbial balance: either the apical extrusion of debris during instrumentation, or the overinstrumentation of the apical foramen resulting in an increased nutrient supply to the bacteria in the canal system.8-10 Siqueira asserted the former to be the more likely circumstance while flare-ups from overinstrumentation result from mechanical injury coupled with bacterial extrusion.9 The findings of a study by Trope that compared the effects of various intracanal medicaments supports this theory, as the incidence of flare-ups was found to be independent of the medicament placed.11 In a study exploring the relationship between bacterial isolate quantity and interappointment flare-up, Chávez found Fusobacterium nucleatum to be a key pathogen.10 In this study of 28 patients seeking emergency treatment after NSRCT, root canal samples were obtained to analyze the quantity of bacterial isolates. Patients with severe interappointment pain were found to correlate with isolates yielding F nucleatum when compared with patients who presented with less-severe pain. The author concluded that F nucleatumis a contributor (in combination with Prevetolla and Porphyomonas species) to endodontic flare-ups. Beyond biochemical processes, Seltzer et al suggested that there may also be psychological factors at play that lower pain threshold, particularly prior traumatic dental experiences.8,12,13

Risk Factors

Although numerous predictors of endodontic flare-ups have been proposed, various risk factors with inconsistent support in the literature make it difficult for providers to accurately anticipate patients who will experience an episode. Common predictors that have been implicated include age, sex, tooth type, initial treatment versus retreatment, number of visits to complete treatment, allergies, presence of preoperative pain, preoperative analgesic use, and periapical presentation.14

Age and sex as risk factors of flare-up are controversial. Retrospective studies done by Torabinejad et al and Nair et al found that women over the age of 40 were at increased risk, whereas several other studies have shown no significant difference in the incidence of flare-up regarding age and sex.1,14-18 The number of sessions taken to complete treatment is another controversial predictor. While Onay et al found that treatment across multiple visits increased the likelihood of flare-up compared to single-visit treatment, the preponderance of evidence suggests no significant association.1,4,15,16,18 It is possible that the association between multi-visit treatment and endodontic flare-up may be confounded by the disease progression and complexity inherent in teeth receiving multi-visit treatment.Other patient factors, including atopy, have been associated with flare-up risk.14

Torabinejad et al and Alaçam et al have shown that mandibular teeth are at increased risk of flare-up, with the theory that the accumulation of inflammatory exudate creates a greater degree of pressure due to the thickness of the mandibular cortical plate.14,17 Torabinejad et al also found that retreatment cases had a high incidence of interappointment flare-up, but this is also a controversial risk factor as several studies report differing results.1,4,14,18 Greater preoperative pain and analgesic use have strong evidence to support their association in higher flare-up risk.1,19

The presence of a periapical lesion has had mixed support. Iqbal et al reported an increased risk in the presence of a radiolucent lesion,4,16,20 whereas Torabinejad's findings suggested the opposite.14 A recent study by Nosrat et al examined factors associated with flare-ups following endodontic retreatments.21 While diabetes mellitus was associated with increased incidence, hypertension was accompanied by a decreased risk of flare-up, neither of which have previously been reported in the literature.21

Prevention

While flare-ups can be unpredictable beyond the risk factors previously discussed, there are certain measures that can be taken in terms of operative technique and pharmacologic treatment that may reduce their likelihood and severity. As extrusion of debris and irrigant can cause a flare-up, working lengths should be confirmed with an electronic apex locator to avoid overinstrumentation. The crown-down technique has been shown to enhance the removal of debris coronally, thereby minimizing risk of flare-up caused by apical extrusion of infected debris.9 Gondim et al showed significantly less postoperative pain in teeth that were irrigated with a negative-pressure device compared to teeth irrigated with a conventional needle syringe, thought to stem from avoidance of apical tissue damage via extrusion of the chemical irrigant.7 A meta-analysis by Silva et al consolidated evidence that foraminal enlargement increases postoperative pain, and they advised caution when considering this technique.22 Several studies show that calcium hydroxide (CH), when used in combination with chlorhexidine (CHX), is more effective in controlling postoperative pain than CH alone. This is thought to derive from CHX's superior efficacy against Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans as well as from its physical properties (eg, pH, ability to spread across dentin surfaces, diffusability).23-25

A randomized clinical trial by Jorge-Araújo et al evaluated post-endodontic pain in patients who were premedicated with oral anti-inflammatory agents.26 Patients were either premedicated with 400 mg of ibuprofen 15 minutes before initiating treatment or 8 mg of dexamethasone 1 hour before initiating treatment. The results of the study found that premedicating with dexamethasone or ibuprofen resulted in significantly reduced postoperative pain compared to placebo. There was no significant difference found between the dexamethasone and ibuprofen treatment groups, suggesting that both are reasonable preventive agents in appropriate patients. Prophylactic antibiotics for the purpose of avoiding flare-up should be avoided, as this practice is not supported by current literature.27,28

Treatment

As described earlier, multiple factors outside of the practitioner's control may contribute to the development of a flare-up; therefore, flare-ups are not always avoidable. When a flare-up occurs, several treatment approaches, often in combination, should receive consideration, including localized treatment, systemic medications, and management of the patient's psychological needs (Figure 1).

A flare-up presenting with swelling may find significant relief after drainage of the exudate, through either recleaning and medicating the canal or incision and drainage. When reinstrumenting, working length and patency should be reassessed. A temporary restoration should be placed over the access opening to avoid exposure of the canal system to microorganisms in the oral cavity, which could exacerbate the flare-up.29-31 Evidence is lacking to support the use of intracanal medicaments such as camphorated monochlorophenol or formocresol for the treatment of flare-ups,14,32,33 while some studies have demonstrated reduced post-NSRCT pain scores with intracanal use of corticosteroid solutions.34,35 Long-acting local anesthetics, such as bupivacaine, can also be used in managing unremitting pain.36

Management of flare-up-associated pain with oral analgesics and steroids has been shown to be effective. Systemic corticosteroids, though effective at dampening the inflammatory response and addressing flare-up-associated pain, carry greater risks than those imposed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and should be carefully considered in the context of the patient's relevant medical history.37 Fortunately, the efficacy of NSAIDs in controlling postoperative endodontic pain is well-supported in the literature.27 Antibiotics are not indicated for pain management without signs or symptoms of infection, such as fever or other evidence of systemic spread.38

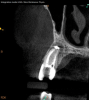

Lastly, regardless of the treatment approach pursued, it is essential to tend to the psychological needs of the patient experiencing a flare-up. The patient should be reassured that the condition is treatable and that flare-ups are quite distinct from treatment failure. In fact, their occurrence has not been shown to affect the overall prognosis of NSRCT (Figure 2 through Figure 5).39,40 Because significant preoperative pain complaints have been associated with a greater risk of flare-up, these patients should be counseled and duly warned of the possible occurrence of a flare-up. Simple discussions on pain management and after-hours emergency availability can significantly reduce the stress of flare-ups for providers and patients alike.14

Conclusion

Flare-ups are a rare but trying complication of root canal therapy that result from a combination of chemical, mechanical, and microbial factors. It can be difficult for providers to accurately predict their occurrence as multiple risk factors have been reported in the literature with varying support. Although flare-ups are unpredictable, preventative measures can be taken to avoid chemical or mechanical injury that may result in exacerbated postoperative pain. Despite one's best attempt to reduce the likelihood, many providers will encounter a flare-up. When this happens it is important to reassure the patient that the event has no bearing on the outcome of the procedure and to utilize local and systemic treatment when appropriate.

About the Authors

Mona Meshkin, DMD

Clinical Fellow, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; Department of Dentistry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Rebekah Lucier Pryles, DMD, Certificate in Endodontics

Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Endodontics, Tufts University School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; Lecturer, Department of Restorative Dentistry and Biomaterials Science, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston,Massachusetts; Private Practice limited to Endodontics, White River Junction, Vermont

Brooke Blicher, DMD, Certificate in Endodontics

Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Endodontics, Tufts University School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; Lecturer, Department of Restorative Dentistry and Biomaterials Science, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston,Massachusetts; Private Practice limited to Endodontics, White River Junction, Vermont

Queries to the author regarding this course may be submitted to authorqueries@broadcastmed.com.

References

1. Walton R, Fouad A. Endodontic interappointment flare-ups: a prospective study of incidence and related factors. J Endod. 1992;18(4):172-177.

2. Nixdorf DR, Law AS, John MT, et al; National Dental PBRN Collective Group. Differential diagnoses for persistent pain after root canal treatment: a study in the National Dental Practice-based Research Network. J Endod. 2015;41(4):457-463.

3. Gotler M, Bar-Gil B, Ashkenazi M. Postoperative pain after root canal treatment: a prospective cohort study. Int J Dent. 2012;2012:310467.

4. Iqbal M, Kurtz E, Kohli M. Incidence and factors related to flare-ups in a graduate endodontic programme. Int Endod J. 2009;42(2):99-104.

5. Tsesis I, Faivishevsky V, Fuss Z, Zukerman O. Flare-ups after endodontic treatment: a meta-analysis of literature. J Endod. 2008;34(10):1177-1181.

6. Oginni AO, Udoye CI. Endodontic flare-ups: comparison of incidence between single and multiple visit procedures in patients attending a Nigerian teaching hospital. BMC Oral Health. 2004;4(1):4.

7. Gondim E Jr, Setzer FC, Dos Carmo CB, Kim S. Postoperative pain after the application of two different irrigation devices in a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Endod. 2010;36(8):1295-1301.

8. Seltzer S, Naidorf IJ. Flare-ups in endodontics: I. Etiological factors. 1985. J Endod. 2004;30(7):476-481.

9. Siqueira JF Jr. Microbial causes of endodontic flare-ups. Int Endod J. 2003;36(7):453-463.

10. Chávez de Paz Villanueva LE. Fusobacterium nucleatum in endodontic flare-ups. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93(2):179-183.

11. Trope M. Relationship of intracanal medicaments to endodontic flare-ups. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1990;6(5):226-229.

12. Rankin JA, Harris MB. Dental anxiety: the patient's point of view. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109(1):43-47.

13. O'Keefe EM. Pain in endodontic therapy: preliminary study. J Endod. 1976;2(10):315-319.

14. Torabinejad M, Kettering JD, McGraw JC, et al. Factors associated with endodontic interappointment emergencies of teeth with necrotic pulps. J Endod. 1988;14(5):261-266.

15. Onay EO, Ungor M, Yazici AC. The evaluation of endodontic flare-ups and their relationship to various risk factors. BMC Oral Health. 2015;

15(1):142.

16. Alves Vde O. Endodontic flare-ups: a prospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110(5):e68-e72.

17. Alaçam T, Tınaz AC. Interappointment emergencies in teeth with necrotic pulps. J Endod. 2002;28(5):375-377.

18. Nair M, Rahul J, Devadathan A, Mathew J. Incidence of endodontic flare-ups and its related factors: a retrospective study. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2017;7(4):175-179.

19. Imura N, Zuolo ML. Factors associated with endodontic flare-ups: a prospective study. Int Endod J. 1995;28(5):261-265.

20. Magar SS Sr, Alfayyadh AY, Alruwaili KK, et al. The determination of flare-up incidence and associated risk factors during endodontic treatment: an observational retrospective study. Cureus. 2022;14(11):e31424.

21. Nosrat A, Valancius M, Mehrzad S, et al. Flare-ups after nonsurgical retreatments: incidence, associated factors, and prediction. J Endod. 2023;49(10):1299-1307.e1.

22. Silva EAB, Guimarães LS, Küchler EC, et al. Evaluation of effect of foraminal enlargement of necrotic teeth on postoperative symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod. 2017;43(12):1969-1977.

23. Singh RD, Khatter R, Bal RK, Bal CS. Intracanal medications versus placebo in reducing postoperative endodontic pain-a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Braz Dent J. 2013;24(1):25-29.

24. Hegde VR, Jain A, Patekar SB. Comparative evaluation of calcium hydroxide and other intracanal medicaments on postoperative pain in patients undergoing endodontic treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Conserv Dent. 2023;26(2):134-142.

25. Sinhal TM, Shah RRP, Shah NC, et al. Comparative evaluation of 2% chlorhexidine gel and triple antibiotic paste with calcium hydroxide paste on incidence of interappointment flare-up in diabetic patients: a randomized double-blinded clinical study. Endodontology. 2017;29(2):136-141.

26. Jorge-Araújo ACA, Bortoluzzi MC, Baratto-Filho F, et al. Effect of premedication with anti-inflammatory drugs on post-endodontic pain: a randomized clinical trial. Braz Dent J. 2018;29(3):254-260.

27. Zanjir M, Sgro A, Lighvan NL, et al. Efficacy and safety of postoperative medications in reducing pain after nonsurgical endodontic treatment: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Endod. 2020;46(10):1387-1402.e4.

28. Shamszadeh S, Asgary S, Shirvani A, Eghbal MJ. Effects of antibiotic administration on post-operative endodontic symptoms in patients with pulpal necrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Rehabil. 2021;48(3):332-342.

29. Seltzer S, Naidorf IJ. Flare-ups in endodontics: II. Therapeutic measures. 1985. J Endod. 2004;30(7):482-488.

30. Weine FS, Healey HJ, Theiss EP. Endodontic emergency dilemma: leave tooth open or keep it closed? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975;40(4):531-536.

31. August DS. Managing the abscessed open tooth: instrument and close-part 2. J Endod. 1982;8(8):364-366.

32. Maddox DL, Walton RE, Davis CO. Incidence of posttreatment endodontic pain related to medicaments and other factors. J Endod. 1977;3(12):447-457.

33. Kleier DJ, Mullaney TP. Effects of formocresol on posttreatment pain of endodontic origin in vital molars. J Endod. 1980;6(5):566-569.

34. Moskow A, Morse DR, Krasner P, Furst ML. Intracanal use of a corticosteroid solution as an endodontic anodyne. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58(5):600-604.

35. Negm MM. Intracanal use of a corticosteroid-antibiotic compound for the management of posttreatment endodontic pain. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92(4):435-439.

36. Dunsky JL, Moore PA. Long-acting local anesthetics: a comparison of bupivacaine and etidocaine in endodontics. J Endod. 1984;10(9):457-460.

37. Shamszadeh S, Shirvani A, Eghbal MJ, Asgary S. Efficacy of corticosteroids on postoperative endodontic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod. 2018;44(7):1057-1065.

38. AAE position statement: AAE guidance on the use of systemic antibiotics in endodontics. J Endod. 2017;43(9):1409-1413.

39. Sjogren U, Hagglund B, Sundqvist G, Wing K. Factors affecting the long-term results of endodontic treatment. J Endod. 1990;16(10):498-504.

40. Friedman S. Prognosis of initial endodontic therapy. Endod Top. 2002;2(1):59-88.