You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

Dental care during pregnancy is not only safe but essential.1 However, communication and referral among healthcare providers is often challenging. In a 2009 national survey of 351 OB/GYNs, 77% reported that some of their patients had been declined dental services due to pregnancy.2 Many women do not seek care based on their perceptions of its appropriateness and safety, as only 42% of women know it is safe to receive dental care during pregnancy.3 They, therefore, may not realize the risks to the overall health of their pregnancy. Additionally, many medical providers fail to, or are unable to, accurately check pregnant patients for oral conditions and refer them for dental care.1 At least 40% of pregnant women experience some form of periodontal disease, including gingivitis, periodontitis, or pyogenic granuloma (benign growth of vascular tissue in pregnancy, or "pregnancy tumor").2,4,5 Furthermore, dietary changes, including those brought on through cravings, and acid exposure secondary to pregnancy-related "morning sickness" (hyperemesis gravidarum) and gastric reflux can increase susceptibility to both dental caries and erosive tooth wear.

Current Recommendations for Dental Care in Pregnancy

The National Maternal and Child Health Resource Center (NMCHRC) recommends that pregnant patients or those seeking to become pregnant who have not seen a dentist in at least 6 months should be referred for dental care,1and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advises OB/GYNs to check patients for oral health issues at their first prenatal visit and make the appropriate referrals.6 Routine dental care such as prophylaxis and the administration of local anesthetic (with or without epinephrine) during pregnancy has not been shown to change rates of miscarriage or birth defects.1,7 Dental radiographs are also safe, although it has been suggested they should be limited for use in a dental emergency, or, if a dental problem needs to be diagnosed, the patient should be appropriately protected with a lead drape.1,7

The consensus statement of NMCHRC states that preventive, diagnostic, and restorative dental treatment is safe throughout pregnancy. For a contemporary review of dental care as a safe and essential part of a healthy pregnancy and for approaches to behavior change in pregnancy, the reader is referred to the previous articles in this series.8,9 The ACOG recommends that any condition that requires immediate dental care can be treated at any time during the pregnancy regardless of trimester.6

(Editor's Note:This is the third offour articles in a series on dental care as part of a healthy pregnancy. The first two articles were published in the February and May issues ofCompendium and are available online at compendiumlive.com/go/cced1848 [Part 1] and compendiumlive.com/go/cced1849 [Part 2]. The fourth article, to be published in early 2019, will focus on the role of the dental team in maternal and child health.)

Interprofessional Collaboration

The Institute of Medicine recommends that all healthcare clinicians "cooperate, collaborate, communicate, and integrate care in teams to ensure that care is continuous and reliable."10,11 Multiple advantages of this 21st century collaborative approach have been reported. The proposed model allows for diagnosis and treatment that fully captures the day-to-day activities needed for continuous and timely delivery of quality patient care; fosters the development of communication skills among providers and between providers and patients/family members; highlights the value of a "good team player," helping the team focus on decreasing the gaps and minimizing the errors in treatment; and allows the providers to develop a more comprehensive understanding of a given problem.12-15

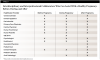

Furthermore, this model encourages knowledge development and helps healthcare providers compile appropriate pathways for referrals, diagnosis, and treatment schemes for existing or new clinical scenarios (Figure 1).16 Table 1 provides a listing of interprofessional and interdisciplinary health professionals, some or all of whom may be involved in prenatal care on a case-by-case basis.

Prenatal Care Health Professionals

In providing guidance for prenatal care health professionals, the National Consensus Statement states that prenatal health professionals may be the first line in assessing pregnant women's oral health and can provide referrals to oral health professionals and reinforce preventive messages.1 During the initial prenatal evaluation, the interview should include assessment items such as: occurrence of vomiting, swollen or bleeding gums, or other mouth problems; date of last dental visit and any incomplete or future-scheduled treatment; and the need for help in finding a dentist. The findings should be documented in the woman's medical record.

The Statement also recommends that the prenatal care health professional should advise pregnant women about oral healthcare. Advice should include: reassurance that oral healthcare, including use of radiographs, pain medications, and local anesthesia, is safe throughout pregnancy; encouragement to seek oral healthcare, practice good oral hygiene, and eat healthy foods; guidance for scheduling a dental appointment if the patient's last dental visit was more than 6 months ago or if any dental problems were identified during the assessment; and instruction that if the patient is unable to receive appropriate treatment, she should monitor any ongoing dental problems and seek treatment as soon as possible if the conditions advance during the pregnancy.

In terms of collaboration, the Statement recommends that prenatal care professionals establish relationships with oral health professionals in the community, develop a formal referral process whereby the dental professional agrees to see the referred individual in a timely manner and provide subsequent care, and share pertinent information and coordinate care with oral health professionals.

Oral Healthcare Professionals

When dental professionals encounter a patient who is either planning to become or has become pregnant they should ask if the patient is under prenatal care. If the patient is not, they should advise the patient to seek prenatal care, assist her through referral if necessary, and then arrange follow-up contact for reinforcement.

Through the spirit and practice of interprofessional collaboration, bidirectional referral relationships become a benefit to all parties, most of all to the patient, but also to both the medical and dental providers as emerging issues are able to be identified and managed in a deliberate sequence enabling improved health outcomes. (See sample scenarios below.)

Maternal Oral Health Changes

All members of the perinatal healthcare team should be aware of pathology that may occur in the oral cavity during pregnancy. Generally, these conditions happen as a result of normal physiological or systemic change and, if not addressed, may impair the longer-term oral health of the woman.

Oral Soft Tissue: Gingivitis and Pyogenic Granuloma

According to the American Academy of Periodontology classification, pregnancy-associated gingival diseases that manifest as a systemic condition include gingivitis and pyogenic granuloma.17 The clinical features of pregnancy gingivitis are consistent with those of gingival conditions associated with plaque biofilm, although the changes in plaque levels may be minimal. Some studies report that when excellent plaque control is maintained, the incidence of pregnancy gingivitis is reduced or absent.18 Increased gingival inflammation can occur due to a more pathogenic bacterial profile of the plaque biofilm and/or an increased response by the patient to the plaque biofilm.19 Despite the severity of the gingival condition, after delivery, resolution of inflammation can be expected to occur in most cases as the body returns to its non-pregnant state.20 Pregnant women with associated underlying medical conditions may expect an exacerbation of the soft-tissue response to the hormonal changes and biofilm pathogenicity.21

Oral Hard Tissue: Non-carious (Tooth-wear) and Carious Lesions

Dental hard tissue can be indirectly affected by the vomiting associated with "morning sickness" (hyperemesis gravidarum) regurgitation and certain food cravings.22,23 Presence of stomach acids in the mouth causes demineralization of both enamel and exposed dentin, which may lead to erosion, particularly on the palatal surfaces of the maxillary dentition. Dietary changes and food cravings may also increase the risk to the hard tissues. Acidic items such as citrus fruits and juices or carbonated beverages may also lead to erosion. Frequent intake of sugar-containing foods and beverages will increase caries risk. Early clinical signs of erosion are smooth and dull enamel surfaces. Later signs are cratering of the cervical areas, cupping of occlusal surfaces, yellowing as enamel thins and dentin subsequently shows through the thinned enamel, and reductions in incisal height.24

Mechanisms and Sequelae of Periodontal Inflammation on Preterm Birth and Delivery

Presence of the characteristic clinical signs and symptoms associated with gingivitis (including increased levels of bacterial pathogens) has been noted in pregnant women when compared to non-pregnant counterparts.25-31 The levels of female gonadotropins during pregnancy correlate with the severity of gingivitis.27-31 Increased levels of progesterone are associated with increased cell membrane permeability, which may contribute to vascular permeability and subsequent edema of gingival tissues.32-34 As the levels of inflamed periodontal tissues increase, the potential for effects of that periodontal inflammation on the maternal-fetal unit may also increase. Periodontal inflammation is known to produce increased secretion of several pro-inflammatory cytokines found in gingival crevicular fluid. Most notably, levels of interleukin (IL)-1b, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-a, and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) are increased.35-39

Furthermore, analyses of serum and amniotic fluid at the time of parturition demonstrate elevated pro-inflammatory markers that have been associated with preterm delivery.38-40 Periodontal pathogens and their virulence factors are able to disseminate systemically and induce local and systemic inflammatory responses in the host.41-43 During pregnancy, these processes can progress to the amniotic cavity and lead to an inflammatory process known as chorioamnionitis. This infection of fetal membranes can quickly spread to the fetus and internal organs of the patient, including the uterus.6 In addition, acid/base changes in the fetus can affect placental tissues and cause disturbances in the maternal-fetal unit. These events can alter fetal development and may lead to premature uterine contractions.43-45

Commonly Undiagnosed Neonatal Oral Conditions

Neonates may present with a variety of conditions, including oral malformation that may affect feeding, swallowing, and speech development; oral manifestations of systemic disease; and benign and/or malignant oral lesions.

Oral Malformations in Neonates

Oral malformation may include anomalies due to failed development and/or fusion of the branchial arches that form the oral cavity. Nearly all of these deformities make feeding difficult and may require correction to improve nutritional intake and sustenance in a neonate.46 Jaw anomalies include failure of mandibular fusion, micrognathia, and Pierre Robin sequence (a triad of u-shaped palatal cleft, micrognathia, and downward tongue displacement [glossoptosis]).46 Lip malformations include lip and/or palatal clefting, microstomia, macrostomia, labial frena, and synechia (adhesion of lip and floor of mouth). Finally, tongue malformations can include macroglossia, ankyloglossia (tongue tie), and lingual thyroid.46

Oral Lesions in Neonates

Oral neonatal lesions include intraoral cysts, infections, traumatic lesions, autoimmune lesions, and tumors. The most common of these are cysts, including: Bohn's nodules, which are salivary-derived keratinocysts with a prevalence of 47.4%; Epstein pearls, which are nonodontogenic keratin-filled and occur in 35.2% of newborns; and gingival/dental lamina cysts, which occur in 13.8% of newborns.47

Infectious lesions may include osteomyelitis of the maxilla, neonatal herpes simplex infection, and neonatal candidiasis.48 Traumatic lesions may occur secondary to birth or feeding injury or because of self-injurious habits, such as lip or finger sucking. These lesions may include mucoceles, ranulae, Riga-Fede disease (associated with natal/neonatal teeth), and breastfeeding keratosis. Finally, tumors may be seen intraorally in the neonatal period and range from common to extremely rare. Nearly 3% of newborns and 30% of low birth-weight/premature neonates demonstrate hemangiomas.48

Other rare benign tumors include lymphangiomas, Langerhans cell histocytosis X, congenital epulis of newborn, melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy, epignathus, and oral choristoma.48 Oral cavity involvement of malignant tumors in neonates has only been reported in two cases: malignant melanoma (hard palate) and spindle cell sarcoma (tongue).48 Because of the complexities of these abnormalities, a close collaboration among all the patient's healthcare professionals is key. Therefore, a bidirectional and interprofessional referral system, including pediatric dentists, neonatologists, and oral pathologists, should be consulted to share expertise for these cases.

Medical and Dental Home Concepts

After delivery it is important for mother and child to access and receive preventive and routine care. The concept of the medical home was first put forward in a policy statement by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1992.49 Key characteristics of the medical home include: (1) a physician known to the child and family who can develop a partnership of mutual trust and responsibility; (2) medical care that is accessible, continuous, family-centered, compassionate, and culturally effective; and (3) care that is delivered or directed by well-trained physicians who provide primary care and can help facilitate all aspects of pediatric care. These characteristics are in contrast to care provided through emergency departments, walk-in clinics, and other urgent care facilities that, though sometimes necessary, is often more costly and less effective.

Strong clinical evidence exists for the efficacy of early professional dental care complemented with caries-risk assessment, anticipatory guidance, and periodic supervision.49 Children who have a dental home are more likely to receive appropriate preventive and routine oral healthcare. The dental home should be established as early as 6 months and no later than 12 months of age, and interval of further visits should be based on risk, providing time-critical opportunities to implement preventive oral health practices. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry recognizes that a dental home should provide comprehensive oral healthcare, including acute care and preventive services, and an individualized preventive dental health program inclusive of risk assessment, dietary counseling, a plan for acute dental trauma, and referral to specialists when care cannot be provided directly within the dental home.49

Conclusion

Routine dental care is both safe and essential before, during, and after a healthy pregnancy. To achieve optimal health outcomes for mother and infant, all health professionals involved in perinatal care, including dental professionals, should cooperate, collaborate, communicate, and integrate care in teams to ensure that care is continuous and reliable. During the period of pregnancy, the physiology of many body systems undergoes changes, leading to pathologies that may manifest themselves in the oral cavity. For the infant, a dental home should be established by the first birthday, and this should include an individualized preventive plan based upon risk.

About the Authors

David C. Alexander, BDS, MSc, DDPH

Adjunct Professor, Epidemiology and Health Promotion, New York University, New York, New York; Principal, Appolonia Global Health Sciences LLC, Green Brook, New Jersey

Maria L. Geisinger, DDS, MS

Associate Professor, Director, Advanced Education Program in Periodontology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama

Sachin Shenoy, MD

Fellow, Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, New York

Irina F. Dragan, DDS, MS

Assistant Professor, Department of Periodontology, and Faculty Practice Provider, Tufts University School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts

Queries to the author regarding this course may be submitted to authorqueries@aegiscomm.com.

Scenario 1:

Visit to Nurse Midwife

A woman presents to her initial appointment with her nurse midwife. According to her last monthly period, she is 8 weeks pregnant. Before becoming pregnant, she was diagnosed with pre-diabetes (impaired glucose tolerance) and hypertension. She has a dentist, but her last dental visit was 8 months ago. As part of the initial examination, the nurse midwife reviews the patient's medical history, including dental history.

Nurse Midwife:

I know you have had high blood pressure and pre-diabetes in the past. Are you checking your blood pressure at home and sticking to a lower-carbohydrate diet?

Patient 1:

I have been checking my blood pressure with a home monitor and have consistently been in the safe zone. My diet has not been great. Morning sickness has started, and toast or crackers are all that I can keep down.

Nurse Midwife:

How frequently have you been vomiting?

Patient 1:

About three or four times per week for the past 3 weeks. It usually occurs in the morning and I try to drink water immediately afterwards to get the acid out of my mouth.

Nurse Midwife:

Have you been experiencing any increase in bleeding gums, tooth pain, or other problems in your mouth?

Patient 1:

I have noticed an increase of blood when I brush and floss, but I am overdue for a dental cleaning. I've been told I shouldn't go until after the baby arrives, though.

Nurse Midwife:

Quite a few dental health conditions can be affected by pregnancy, and your gum bleeding could be a sign of inflammation that may be harmful to your baby. It is important that you see your dentist and make sure your gums and teeth are healthy. Do you have a dentist that you see?

Patient 1:

I have seen Dr. Smith in the past. I liked her, but I don't want to go if they are not going to be able to treat me.

Nurse Midwife:

Let's call Dr. Smith's office and schedule an appointment. I can send over a list of medications that are safe to use during pregnancy, and I will talk with her about some of our concerns.

Scenario 2:

Visit to Dentist

A new patient to a dental office is seeking an examination and "routine cleaning." During the medical history review, she reveals that she does not know if she is currently pregnant and that she and her husband have been trying to become pregnant for 3 months. She recently moved to the area and has not yet seen a local OB/GYN. Her medical history is significant for one other uncomplicated pregnancy and delivery. She recalls that during her last pregnancy she did not see her OB/GYN until 10 weeks, so she states that she is "not in a rush" to find a new one.

Dentist:

It is exciting that you are planning to become pregnant! Did you experience any health problems during your last pregnancy with either your teeth and gums or your overall health?

Patient 2:

My last pregnancy was fairly easy-just had some tiredness and aches and pains. I did experience some bleeding gums, and my previous dentist said it was important for me to continue to have my teeth cleaned during pregnancy. I did not know that, and my OB/GYN was surprised to hear it, too.

Dentist:

Current scientific studies do show that dental care is safe during pregnancy and that routine dental care and good oral hygiene may address the increased risk of gingivitis and other periodontal diseases and the increase in body inflammation seen during pregnancy. We like to work with your OB/GYN while you are trying to get pregnant and during pregnancy to best time dental care and ensure that you are receiving prenatal care to keep you and the baby as healthy as possible. Do you have an OB/GYN in the area yet?

Patient 2:

No, not yet. Do you have any recommendations?

Dentist:

We have worked with several doctors in the area that we can suggest. Once you decide on an OB/GYN, let us know and we will work with you and them to communicate about the best course of treatment, any updates on your health status, including pregnancy, and any dental concerns that we may have. We like to make sure all your care team is communicating and coordinating your care.

Patient 2:

I'll make some phone calls and see someone as soon as possible! I want to do everything I can to keep myself and my future baby healthy, and I like that you have worked with these doctors before and are on the same page with them.

References

1. Oral Health Care During Pregnancy Expert Workgroup. Oral Health Care During Pregnancy: A National Consensus Statement. Washington, DC: National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center; 2012.

2. US Public Health Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health. 2000. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/access/NNBBJT.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2018.

3. Wakefield Children's Dental Health Project. QuickRead Report. February 2015. https://s3.amazonaws.com/cdhp/Wakefield+Survey+for+CDHP+(For+Public).pdf. Accessed October 4, 2018.

4. For the dental patient: oral health during pregnancy. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(5):574.

5. Boggess KA; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee. Maternal oral health in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(4):976-986.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Women's Health Care Physicians; Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee opinion No. 569: oral health care during pregnancy and through the lifespan. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 Pt 1):417-422. (reaffirmed 2017).

7. Hagai A, Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Ornoy A. Pregnancy outcome after in utero exposure to local anesthetics as part of dental treatment: a prospective comparative cohort study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146(8):572-580.

8. Dragan IF, Veglia V, Geisinger ML, Alexander DC. Dental care as a safe and essential part of a healthy pregnancy. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2018;39(2):86-91.

9. Geisinger ML, Dragan IF, Alexander DC. Healthy pregnancy: a patient-centered approach to counseling and behavioral change. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2018;39(5):286-290.

10. Greiner AC, Knebel E, eds. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

11. Kalkwarf KL, Haden NK, Valachovic RW. ADEA commission on change and innovation in dental education. J Dent Educ. 2005;69(10):1085-1087.

12. Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638-645.

13. ten Cate O, Scheele F. Competency-based postgraduate training: can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad Med.2007;82(6):542-547.

14. Chen HC, van den Broek WE, ten Cate O. The case for use of entrustable professional activities in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):431-436.

15. Brooks MA. Medical education and the tyranny of competency. Perspect Biol Med. 2009;52(1):90-102.

16. Hursh B, Haas P, Moore M. An interdisciplinary model to implement general education. J Higher Educ. 1983;54(1):42-59.

17. Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4(1):1-6.

18. Arafat AH. Periodontal status during pregnancy. J Periodontol. 1974;45(8):641-643.

19. Armitage GC. Bi‑directional relationship between pregnancy and periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2013;61(1)160-176.

20. Raber‑Durlacher JE, van Steenbergen TJ, Van der Velden U, et al. Experimental gingivitis during pregnancy and post‑partum: clinical, endocrinological, and microbiological aspects. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21(8):549-558.

21. Otomo‑Corgel J. Dental management of the female patient. Periodontol 2000. 2013;61(1):219-231.

22. Burkhart NW. Preventing dental erosion in the pregnant patient. RDH. January 1, 2012. https://www.rdhmag.com/articles/print/volume-32/issue-1/columns/preventing-dental-erosion-in-the-pregnant-patient.html. Accessed October 4, 2018.

23. Hemalatha VT, Manigandan T, Sarumathi T, et al. Dental considerations in pregnancy - a critical review on the oral care. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(5):948-953.

24. Scheutzel P. Etiology of dental erosion - intrinsic factors. Eur J Oral Sci. 1996;104(2 [Pt 2]):178-190.

25. Maier AW, Orban B. Gingivitis in pregnancy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1949;2(3):334-373.

26. Löe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533-551.

27. Cohen DW, Shapiro J, Friedman L, et al. A longitudinal investigation of the periodontal changes during pregnancy and fifteen months post-partum. II. J Periodontol. 1971;42(10):653-657.

28. Kornman KS, Loesche WJ. The subgingival microbial flora during pregnancy. J Periodontol Res. 1980;15(2):111-122.

29. Tilakaratne A, Soory M, Ranasinghe AW, et al. Periodontal disease status during pregnancy and 3 months post-partum, in a rural population of Sri Lankan women. J Clin Periodontol.2000;27(10):787-792.

30. Taani DQ, Habashneh R, Hammad MM, Batieha A. The periodontal status of pregnant women and its relationship with socio-demographic and clinical variables. J Oral Rehab. 2003;30(4):440-445.

31. Figuero E, Carrillo-de-Albornoz A, Martín C, et al. Effect of pregnancy on gingival inflammation in systemically healthy women: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(5):457-473.

32. O'Neil TC. Plasma female sex-hormone levels and gingivitis in pregnancy. J Periodontol. 1979;50(6):279-282.

33. Raber-Durlacher JE, Zeijlemaker WP, Meinesz AA, Abraham-Inpijn L. CD4 to CD8 ratio and in vitro lymphoproliferative responses during experimental gingivitis in pregnancy and post-partum. J Periodontol. 1991;62(11):663-667.

34. Raber-Durlacher JE, Leene W, Palmer-Bouva CC, et al. Experimental gingivitis during pregnancy and post-partum: immunohistochemical aspects. J Periodontol. 1993;64(3):211-218.

35. Offenbacher S, Jared HL, O'Reilly PG, et al. Potential pathogenic mechanisms of periodontitis associated pregnancy complications. Ann Periodontol.1998;3(1):233-250.

36. Konopka T, Rutkowska M, Hirnle L, et al. The secretion of prostaglandin E2 and interleukin 1-beta in women with periodontal diseases and preterm low-birth-weight. Bull Group Int Rech Sci Stomatol Odontol.2003;45(1):18-28.

37. Li X, Kolltveit KM, Tronstad L, Olsen I. Systemic diseases caused by oral infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13(4):547-558.

38. Gendron R, Grenier D, Maheu-Robert L. The oral cavity as a reservoir of bacterial pathogens for focal infections. Microbes Infect.2000;2(8):897-906.

39. Lafaurie GI, Mayorga-Fayad I, Torres MF, et al. Periodontopathic microorganisms in peripheric blood after scaling and root planing. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34(10):873-879.

40. Kaur M, Geisinger ML, Geurs NC, et al. Effect of intensive oral hygiene regimen during pregnancy on periodontal health, cytokine levels, and pregnancy outcomes: a pilot study. J Periodontol. 2014;85(12):1684-1692.

41. Zhang D, Chen L, Li S, et al. Lipopolysacchride (LPS) of Porphymonas gingivalis induces IL-1beta, TNF-alpha, and IL-6 production by THP-1 cells in a way different from that of Escherichia coli LPS. Innate Immun. 2008;14(2):99-107.

42. Abrahams VM, Bole-Aldo P, Kim YM, et al. Divergent trophoblast responses to bacterial products mediated by TLRs. J Immunol.2004;173(7):4286-4296.

43. Offenbacher S, Lieff S, Boggess KA, et al. Maternal periodontitis and prematurity. Part I: obstetric outcome of prematurity and growth restriction. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6(1):164-174.

44. Gibbs RS, Romero R, Hillier SL, et al. A review of premature birth and subclinical infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(5):1515-1528.

45. Brown NL, Alvi SA, Elder MG, et al. A spontaneous induction of fetal membrane prostaglandin production precedes clinical labour. J Endocrinol. 1998;157(2):R1-R6.

46. Damaré SM, Wells S, Offenbacher S. Eicosanoids in periodontal diseases: potential for systemic involvement. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;433:23-35.

47. Issacson GC. Congenital anomalies of the jaw, mouth, oral cavity, and pharynx. UpToDate Medical Reviews. Updated October 20, 2017. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/congenital-anomalies-of-the-jaw-mouth-oral-cavity-and-pharynx/. Accessed October 4, 2018.

48. Moda A. Gingival cyst of newborn. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent.2011;4(1):83-84.

49. American Academy of Pediatrics Ad Hoc Task Force on Definition of the Medical Home: The medical home. Pediatrics. 1992;90(5):774.