You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

Prescription drugs classified as controlled dangerous substances are widely accepted as essential therapeutic modalities in treating a variety of healthcare conditions. However, many prescription medications have pleasurable side effects that can appeal to patients to take these drugs for uses other than intended. Misuse or abuse of prescription drugs can contribute to addictive behaviors, serious health risks, and potentially, death.1 The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), as well as other state and local agencies across the country, maintains a close watch on trends in prescription drug abuse.1 A news release on March 7, 2007, stated that NIDA, as a component of the National Institutes of Health, initiated its first large-scale national study related to prescription drug abuse, thereby recognizing it as a serious healthcare issue facing the United States.2 More recently, on September 22, 2010, Nora D. Volkow, MD, Director of NIDA, addressed these concerns at the Congressional Caucus on Prescription Drug Abuse. Her testimony indicated that nonmedical use of prescription drugs occurs among 7 million Americans per month. This figure surpassed the number of Americans abusing cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, and inhalants combined.3

It is imperative that the dental community remains educated and informed of nationwide healthcare trends, and prescription drug abuse is no exception. Ethically, dentists should be able to respond in a manner that addresses the best interests of their patients.4 This response needs to include understanding the terminology of prescription drug abuse; identifying and describing the drugs most often misused or abused; identifying individuals who may be at risk for prescription drug abuse; and managing patients at risk in the dental setting.

Related Terminology

NIDA recognizes that the terminology related to the abuse of drugs tends to be applied in "idiosyncratic ways."5 To avoid unnecessary confusion in interpreting the research findings, leaders in the area of drug abuse suggest that study results specify definitions for terms used.5 For the purposes of this article, the definitions used will be those consistent with reports by NIDA.

The introduction of this narrative uses the terms "misuse," "abuse," and "nonmedical use." According to NIDA, the terms "prescription drug abuse" and "nonmedical use" are used interchangeably. The definition of prescription drug abuse used by most national surveys is: "the intentional use of an approved medication without a prescription, in a manner other than how it was prescribed, for purposes other than prescribed, or for the experience or feeling the medication can produce. Misuse refers to unintentional use of an approved medication in a manner other than how it was prescribed."3

A simple example of abuse may be illustrated by a teenage girl who self-prescribes dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine®) to help her "keep her appetite in check." She may report that she "heard diet pills can be dangerous," so she chooses to use her friend's sister's attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medication instead. Another example is the middle-school student who decides to take his brother's unused hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin®) from his recent third molar extraction surgery, simply to "see what happens."

The elderly provide examples of the misuse of prescribed drugs when taking medications in a way that is different from how their doctor prescribes the medication. As poly-medications and complicated prescribing regimens rise, and as confusion increases and mental acuity decreases for some older adults, the odds that medications can be unintentionally misused can increase accordingly.3

In addition to the terms used above, and to further clarify the issues surrounding prescription drug abuse, it is essential to also understand the definitions of "physical dependence," "tolerance," and "psychologically dependent."

Individuals are said to show signs of physical dependence when their bodies respond negatively as the drug in question is discontinued following chronic use. As the body becomes accustomed to the regular use of a substance (either as prescribed or not as prescribed), individuals who are physically dependent on the substance find that they cannot function normally without it. As physical dependence becomes established, the person may develop tolerance, where an increase in the amount of drug taken is required to have the desired effect and prevent withdrawal.6

People who are "psychologically dependent" to a drug (often used synonymously with the term "addicted") appear to have lost their ability to make sound decisions about what may be right or wrong related to their drug use. They report that they "cannot stop without help"; they are chronically compulsive in their drug-seeking behavior despite the physical and emotional health risks involved. At this level, their bodies may be physically dependent on the substance, and despite the adverse consequences they continue to misuse the drug. This disease stage of addiction is characterized by neurochemical and molecular changes in the brain.6

Most Frequently Abused Drugs

Statistics related to emergency room visits support the increasing nationwide trend of prescription drug misuse and abuse. The Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) collects data related to emergency room visits resulting from drug misuse and abuse. DAWN reports revealed that between 2004 and 2006 the total number of hospital visits to emergency departments (EDs) across the United States increased by 3.9%.7 Although the number of drug-related ED visits remained stable during this time, prescription drug-related ED visits increased by 44%.7

This staggering statistic speaks to the epidemic of prescription drug abuse, and how for some drug seekers certain medications appear to be favored over the traditional illicit or "street" drugs. Notably, certain mood-altering prescription drugs set themselves apart from others as having higher addictive potential. Drugs with characteristics that include a rapid onset of action, high purity, high potency, and brief duration appear to be most sought-after by drug seekers. Therefore, drugs like diazepam (Valium®), which crosses the blood-brain barrier rapidly, or alprazolam (Xanax®), which has a short half-life and high potency, are more likely to be abused and have a higher "street value."8 As shown in Table 1, and discussed in detail below, the three most widely abused or misused drug classifications are opioids, central nervous system (CNS) depressants, and stimulants.7

Opioids

Opioid analgesics such as Vicodin® and Percodan® are the most frequently abused of the prescription drugs.7 Referred to as prescription narcotics, opioids are most often prescribed as analgesics for acute or chronic pain but can also be used as anti-tussives or anti-diarrheals, and include codeine and diphenoxylate (Lomotil®), respectively.1 A large number of drugs fit into this category, but the most frequently abused are the hydrocodone and oxycodone products9 (Table 1).

Through their mechanism of action, opioids block the perception of pain when they attach themselves to specific proteins (referred to as opioid receptors) found in the brain, spinal cord, and gastrointestinal tract. Opioids are also known to affect the way the brain perceives pleasure, leading to a state of euphoria. Common side effects of opioid use include nausea, constipation, and drowsiness. High doses of these drugs can also lead to miosis and respiratory depression. When discontinued after prolonged use an individual who has become physically dependent on the drug will display withdrawal symptoms that are opposite from its pharmacological effect, including restlessness (to include involuntary leg movements), insomnia, muscle and bone pain, diarrhea, mydriasis, and cold flashes with goose bumps ("cold turkey").1

Central Nervous System Depressants

Central nervous system (CNS) depressants, sometimes referred to as sedatives or tranquilizers, make up the second-most abused group of prescription drugs, with the benzodiazepines among the most abused of this group. Benzodiazepines, which are prescribed to treat anxiety, acute stress reactions, and panic attacks, include diazepam (Valium®), chlordiazepoxide HCl (Librium®), and alprazolam (Xanax®). More sedating benzodiazepines, used to treat sleep disorders, are triazolam (Halcion®) and estazolam (ProSomTM). The barbiturates that are used to treat sleep disorders include mephobarbital (Mebaral®) and pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal®) (Table 1).

Most CNS depressants increase the activity of the brain's neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which inhibits neuronal function. As a result, when individuals first take CNS depressants as directed, they report feeling sluggish, possibly disoriented, and drowsy. However, as their dose is adjusted and their bodies begin to become accustomed to the drug, these symptoms routinely resolve. Long-term use of these drugs can lead to physical dependence and tolerance. As this occurs, individuals find they require a higher dose to get the desired effect. When the drug is removed, the person can experience significant rebound or withdrawal symptoms which are opposite from its pharmacological effect that may lead to complications as a result of increased rebound-like brain activity, such as agitation, insomnia, and seizures.1

Stimulants

Stimulants, including dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine® and Adderall®) and methylphenidate (Ritalin® and Concerta®), represent the third group of most-frequently abused prescription drugs, and are prescribed for ADHD, narcolepsy, and depression that has not responded to other treatment modalities. In response to their discovered abuse and addiction potential, use of this group of drugs for conditions such as obesity, asthma, and other respiratory problems has decreased.1 These drugs are classified by the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) as scheduled substances according to their abuse potential (Table 1).

Central nervous system neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine are enhanced by the use of prescription stimulants, resulting in an intensified feeling of energy and euphoria. However, feelings of hostility and paranoia may surface from those who repeatedly abuse stimulants over a short period of time. Additional dangerous effects related to the use of stimulants, especially in high doses, include extremely high body temperature/seizures and an irregular heartbeat/cardiovascular failure. Fatigue, depression, and disturbance of sleep patterns, which, as previously noted, are opposite from the abused drugs' pharmacological effect, can occur when stimulant use is discontinued.1

Risk for Prescription Misuse and Abuse

In an effort to address the prescription drug abuse issue, it becomes critical that those at risk for misuse and abuse be identified. According to the literature, certain groups appear to be more at risk than others. NIDA's recent congressional report, through data from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), identifies young adults age 18 to 25 as the group with the highest percentage of nonmedical use of prescription drugs in past-month users.3 A current trend in this age group is the use of stimulants prescribed to treat ADHD. College students are relying on these "legal" drugs to help them "focus" on their studies.10 Data also shows, however, that past-year users in the 12-17-year-old age group are more likely to become dependent on the psychotherapeutic drugs used when compared to young adults. In this 12-17-year-old age group, females have been shown to be more likely to participate in the nonmedical use of pain relievers, tranquilizers, and stimulants than males in the same group, and are more likely to be dependent on stimulants.3 Data from the 2009 Monitoring the Future survey (MTF) reports that 8 of the top 14 categories of drugs abused by 12th graders are both prescription, particularly opioids, and over-the-counter drugs. Through the MTF data, 1 in 10 high-school seniors have reported nonmedical use of Vicodin® and 1 in 20 report the same for OxyContin®.3

In addition to women and adolescents, a growing population of individuals at high risk for developing prescription drug abuse is seniors, or those over 65 years of age. NIDA's 2005 report cited above also states that this population comprises "only 13% of the population, yet accounts for approximately one-third of all medications prescribed in the United States."1 This group of patients is known to metabolize drugs differently than younger patients. Additionally, as a result of their medical histories, these patients are often taking multiple medications that when used together can confound adverse reactions, lead to confusion regarding proper use, and potentiate unwanted dependence. Seniors often seek the care of multiple physicians who may offer repeat prescriptions for the same medical issue. Additionally, increased cognitive impairment, coupled with the CNS effects of medications, can result in unfortunate falls or accidents, leading to more severe health-related issues and potentially requiring more prescription drugs.1,11

Although it is important that the healthcare team remain cognizant of the more recent trends of populations at risk for addiction to prescription drugs, it is also critical to recall the other populations who have more traditionally identified themselves at risk for addictive patterns across all demographics.12 Those at risk have reported histories that include, but are not limited to, the following: severe stress, past addiction, a family member (genetic link) who has revealed addictive behaviors, or emotional trauma and/or depression.13

In addition to these risk factors, other patient characteristics may also prove to be "red flags" that can alert the practitioner to the possibility of prescription drug abuse. For example, a medical history may include a complexity of ailments and/or that of an "allergy" to certain nonsteroidal or nonprescription analgesic drugs. Moreover, a request for a certain drug by name, describing it as the only drug that can alleviate the pain, may be presented. A report that the prescription has been "lost" or that it was left in luggage that was "lost" in travel may surface. These reports are often accompanied by complicated time constraints related to appointments; these and other "stories" may even be substantiated by a friend or family member who is also present in the office.13

Access to Prescription Drugs and Prescribing Practices

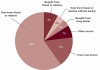

Studies report that there is an inherent ease in the acquisition of prescription drugs, leading to their increased misuse and abuse14,15 (Figure 1). Teenagers report family and friends as easy targets for drugs left unattended in medicine cabinets and closets.14 In 2008, presumably in an effort to raise awareness, the Office on National Drug Control Policy aired prime-time television commercials depicting a student-actor at the lunch table describing his "stash" to the viewer—explaining whose medicine cabinet he "lifted" each pill from.16

Contributing to this issue is the fact that prescription drugs are legal substances, thereby providing abusers with the rationalization that abusing them does not break the law. In some way the perceived threat may be less than it would be if an illegal substance was involved, conveniently blurring the fact that misusing prescription drugs is also illegal.15

Perhaps leading to its availability for abuse, opioid analgesics are some of the most frequently prescribed drugs in the United States. For the management of severe pain, prescriptions formulated with the opioids hydrocodone, oxycodone, codeine, or propoxyphene (removed from the market by the US Food and Drug Administration November 2010) are commonly prescribed. These four opioids, usually formulated in combination with acetaminophen, were ranked 1st, 20th, 35th, and 58th, respectively, among the 200 most frequently prescribed drugs in 2008.17

Specific to the dental community, a survey of the analgesics prescribed by practicing oral surgeons found similar results when selecting opioids for postoperative pain management. Among those who responded to this national survey, the most common analgesic prescriptions written to manage postoperative pain following the extraction of third molars were the combination of hydrocodone with acetaminophen (Vicodin®, Lorcet®, etc) and the combination of oxycodone with acetaminophen (Percocet®, Roxicet®). Instruction for use almost always directed the patient to take these analgesics "as needed" for pain. The average number of tablets dispensed following the removal of third molars was 20 tablets.18 A 2-day conference in 2010 titled "Tufts Health Care Institute's Program on Opioid Risk Management" presented literature supporting the belief that the quantities of opioid analgesics prescribed for the management of postoperative pain are often greater than that required for pain relief.19

Although oral surgeons were found to prescribe on average 20 tablets of Vicodin or Percocet, significantly fewer (ie, 8 to 12 tablets) are likely required or used by most surgical dental patients. Unused drugs left in a medicine cabinet certainly have the potential for misuse. If severe pain continues beyond this regimen, infection or impaired healing are likely, and a return visit to the dentist is usually indicated. Alternatively, several therapeutic drug strategies have been shown to limit postoperative dental pain and the need for opioid-combination analgesics. These include greater reliance on full therapeutic doses of second-generation nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (ie, ibuprofen 400 to 600 mg and naproxen 50 mg)20; combining NSAIDs with N-Acetyl-P-Aminophenol (APAP)21; administering newer NSAID analgesics immediately prior to surgery22,23; providing intravenous glucocorticoidsteroids when indicated24; and prolonging the onset of postoperative pain by using the long-acting agent bupivacaine.25,26

Controversy has been reported related to the effect that Internet pharmacies may have on the prescription drug abuse issue. Access to prescription drugs through this route appears to be under debate and close scrutiny. As it relates to online prescription drug access, McCarthy wrote that a 2006 study conducted by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University identified during a 1-week search 185 websites selling commonly abused prescription drugs. At the time, it was reported that 9 out of 10 sites appeared to not require prescriptions, while 30 of those sites actually advertised the fact that prescriptions were not necessary.14 However, in 2008, Cicero et al refuted much of this claim in their study and concluded that the ease of online access prescription medications "appears to be based on no empirical evidence."27

Managing Prescription Drug Abusers in the Dental Setting

Healthcare teams are in the position to identify and treat a growing population of patients who are afflicted with drug-related disorders. NIDA's revised August 2005 Research Report Series expounds on the role physicians can have on helping to prevent, identify, and assist their patients in getting the support they need when faced with a drug-related disorder. The report goes on to outline that since 70% of Americans seek the care of their primary physician at least once every 2 years, these physicians are in a unique position to be of service to their patients who may be abusing drugs.1 The report does not, however, highlight the role the dentist can have on the same population. It is widely accepted that the recommended standard of dental care is to recall patients at least every 6 months to reduce the risk of oral disease. With this timetable in mind, the average dentist may find him/herself in the role of being among the first of the healthcare team to identify and assist the patient who is abusing prescription drugs.

As written in the American Dental Association (ADA) Principles of Ethics and Code of Professional Conduct (section 2.A.), dentists have the obligation to keep "their knowledge and skill current" to best serve their patients and society. This includes keeping abreast of current trends in prescription drug abuse.4 As healthcare providers, we have been trained to "never treat a stranger." In doing so, as the dental team serves to address the needs of their patients, they can first gather critical information that will allow them to learn more about their patients' risks for drug abuse. While obtaining a thorough history (to include asking about addiction/recovery history) and physical examination, the dental team has the ability to obtain additional information, observe body language and overall presentation, and develop healthy and trusting doctor-patient relationships.

Resources

In April 2009, specifically to assist the healthcare community, NIDA launched a website targeted at medical and health professionals termed "NIDAMED."28 This site provides valuable resources, including videos related to building trust in the doctor-patient relationship; access to the "NIDA Centers of Excellence for Physician Information" (American Medical Association collaborative efforts with NIDA); treatment and prevention literature, including clinical trials; and access to the "NIDA Networking Project," an opportunity for interested healthcare providers to exchange and collaborate on research.

In an effort to help practicing healthcare providers better inform their patients about drug misuse and abuse, patient information literature for both adults and youth is also accessible from the NIDAMED site. Use of the "NIDA-Modified Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (NMASSIST)" may also be considered by the healthcare provider as a helpful in-office screening measure. This quick online screening tool assists healthcare providers in identifying those patients who may be at risk for substance abuse of any kind. Patients can be asked to take this online survey in the office and the results can be reviewed with the healthcare provider immediately. The calculated risks of use and/or addictive potential are based on a scale of "high," "moderate," or "low" risk. As each rating related to the specific patient is revealed, online resources to include "Conducting a Brief Intervention," "Recommendations to Address Patient Resistance," and "Sample Progress Notes" can be easily accessed through provided links. The results also offer the healthcare provider support information, including when it may be appropriate to counsel the patient in the office, when it is necessary to refer the patient for external specialized care related to their habits or risk, and how to access these centers.28

Through the use of a computer-based search process, drug abuse patient counseling resources are easily accessible, making it simple for providers to find the necessary help for their patients. When faced with a patient who is interested in help related to their addiction problem, the healthcare provider can quickly identify a nearby counseling center. Thanks to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (as a branch of the US Department of Health and Human Services), a simple electronic search can help locate these centers across the country. The Substance Abuse Treatment Facility Locator can be easily accessed from the NIDAMED site.28 Users who provide login location information gain access to all treatment facilities in their area according to the chosen mile radius. This search also provides helpful information related to the facilities' locations, phone numbers, primary focus of services provided, outpatient versus inpatient capabilities, payment assistance programs/accepted forms of payment, special language/disability services provided, and website accessibility.

Conclusion and Recommendations

It is critical that dentists be well-versed in the terminology and risk factors associated with prescription drug abuse and be able to offer guidance and support when faced with a patient at risk of drug abuse. As a participant in the "Tufts Health Care Institute's Program on Opioid Risk Management" conference in November 2008, the ADA has posted a summary of its findings. This collaboration has provided information to include a list of goals to help address the prescription drug abuse issue. The ADA's work includes written guidelines for opioid use and a research agenda to assist other agencies.29 The literature presented during this symposium supported the belief that the quantities of opioid analgesics prescribed for the management of postoperative pain are often more than usually needed.

Through medical and drug histories, the dental community may be able to identify possible abusers, communicate with patients in recovery, consider alternatives for pain control, inform patients not to share their medications with anyone, and alert patients (and parents) to maintain secure storage and dispose of excess drugs properly (Table 2). It is critical for dentists to be informed of these nationwide outcomes and professional expectations related to the issue of prescription drug abuse in order to continue to provide the best treatment to their patients as they service the community.

References

1. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Research Report Series. Prescription Drug Abuse and Addiction. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/ResearchReports/Prescription/Prescription.html. Accessed November 13, 2010.

2. National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA Launches First Large-Scale National Study to Treat Addiction to Prescription Pain Medications. Available at: http://archives.drugabuse.gov/newsroom/07/NR3-07a.html. Accessed November 13, 2010.

3. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Congressional Caucus on Prescription Drug Abuse. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/Testimony/9-22-10Testimony.html. Accessed November 13, 2010.

4. American Dental Association. Principles of Ethics and Code of Professional Conduct. Available at: http://www.ada.org/sections/about/pdfs/ada_code.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2010.

5. Compton WM, Volknow ND. Abuse of prescription drugs and the risk of addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83(suppl 1):S4-S7.

6. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Media Guide. The Basics: The Science of Drug Abuse and Addiction. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/mediaguide/scienceof.html. Accessed November 13, 2010.

7. National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA Info-Facts Drug-Related Hospital Emergency Room Visits. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/infofacts/HospitalVisits.html. Accessed November 14, 2010.

8. Longo LP, Parran T Jr, Johnson B, Kinsey W. Addiction: part II. Identification and management of the drug-seeking patient. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(8):2401-2408.

9. Cicero TJ, Inciardi JA, Munoz A. Trends in abuse of Oxycontin and other opioid analgesics in the United States: 2002-2004. J Pain. 2005;6(10):662-672.

10. U.S. Department of Education's Higher Education Center for Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Violence Prevention. Recreational Use of Ritalin on College Campuses. Available at: http://www.higheredcenter.org/services/publications/recreational-use-ritalin-college-campuses. Accessed November 23, 2010.

11. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Confronting the Rise in Abuse of Prescription Drugs. Available at: http://archives.drugabuse.gov/NIDA_notes/NNvol19N5/DirRepVol19N5.html. Accessed November 15, 2010.

12. Diogo S. When your patient is an addict: understanding addiction and recovery issues can help you better manage your patients and protect your practice. AGD Impact. 2003:12-16.

13. Rosco MS. The drug seeking patient: undertreated pain or underhanded motives? Clinician Reviews. 2004;14(2).

14. McCarthy M. Prescription drug abuse up sharply in the USA. Lancet. 2007;369(9572):1505-1506.

15. Manchikanti L. National drug control policy and prescription drug abuse: facts and fallacies. Pain Physician. 2007;10(3):399-424.

16. Office on National Drug Control Policy. Teens and Prescription Drugs: All My Pills. Available at: http://www.theantidrug.com/drug-information/otc-prescription-drug-abuse/prescription-drug-tv-ads-videos/all-my-pills-transcript.aspx. Accessed November 15, 2010.

17. Wynn RL, Meiller TF, Crossley HL. Top 200 most prescribed drugs in 2008. In: Drug Information Handbook for Dentistry. 15th ed. Wynn RL, Meiller TF, Crossley HL, eds. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp; 2009:2064-2065.

18. Moore PA, Nahouraii HS, Zovko JG, Wisniewski SR. Dental therapeutic practice patterns in the U.S. II. Analgesics, corticosteroids, and antibiotics. Gen Dent. 2006;54(3):201-207.

19. Tufts Health Care Institute Program on Opioid Risk Management. Executive Summary: The Role of Dentists in Preventing Opioid Abuse. Tufts Health Care Institute Program on Opioid Risk Management 12th Summit Meeting. March 11-12, 2010. Available at: www.thci.org/opioid/mar10docs/executivesummary.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2010.

20. Barden J, Edwards JE, McQuay HJ, et al. Relative efficacy of oral analgesics after third molar extraction. Br Dent J. 2004;197(7):407-411.

21. Ong CK, Seymour RA, Lirk P, Merry AF. Combining paracetamol (acetaminophen) with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: a qualitative systematic review of analgesic efficacy for acute postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(4):1170-1179.

22. Dionne RA, Campbell RA, Cooper SA, et al. Suppression of postoperative pain by preoperative administration of ibuprofen in comparison to placebo, acetaminophen, and acetaminophen plus codeine. J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;23(1):37-43.

23. Jackson DL, Moore PA, Hargreaves KM. Preoperative nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication for the prevention of postoperative dental pain. J Am Dent Assoc. 1989;119(5):641-647.

24. Moore PA, Brar P, Smiga ER, Costello BJ. Preemptive rofecoxib vs. dexamethasone for prevention of pain and trismus following third molar surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99(2):E1-E7.

25. Gordon SM, Mischenko AV, Dionne RA. Long-acting local anesthetics for perioperative pain management. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54(4):611-620.

26. Moore PA. Bupivaciane: a long-lasting local anesthetic for dentistry. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58(4):369-374.

27. Cicero TJ, Shores CN, Paradis AG, Ellis MS. Source of drugs for prescription opioid analgesic abusers: a role for the Internet? Pain Med. 2008;9(6):718-723.

28. National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDAMED Resources for Medical and Health Professionals. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/nidamed/. Accessed November 15, 2010.

29. American Dental Association. Dentists seek to curb abuse when helping patients. Available at: http://www.ada.org/news/4227.aspx. Accessed November 15, 2010.

About the Authors

Marnie Oakley, DMD

Assistant Professor and Chair

Restorative Dentistry/Comprehensive Care

Assistant Dean for Clinical Affairs

University of Pittsburgh

School of Dental Medicine

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Jean O'Donnell, DMD

Assistant Professor and Vice Chair

Restorative Dentistry/Comprehensive Care

Assistant Dean for Education and Curriculum

University of Pittsburgh

School of Dental Medicine

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Paul A. Moore, DMD, PhD, MPH

Professor and Chair, Department of Dental Anesthesiology

University of Pittsburgh

School of Dental Medicine

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

James Martin, DMD

Recent graduate, University of Pittsburgh

School of Dental Medicine

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania