You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is considered to be a nearly ideal clinical sedative.1 Originally deemed a failure after a substandard demonstration by Horace Wells at Harvard Medical School in 1845, this chemical compound is now one of the most widely used anesthetics in dentistry.

Often known as “laughing gas,” nitrous oxide is a colorless, odorless gas used to induce a state of euphoria and has been employed in clinical dentistry for more than 150 years.1 It has become a cornerstone of pharmacological behavior management and rapid analgesia. Its role has evolved significantly, transitioning from an early solo technique to its current use in a diluted solution. In modern practice, nitrous oxide is titrated with oxygen to achieve its desired euphoric and tranquillizing effects, whereas its historical use primarily focused on inducing analgesia.2 Today, nitrous oxide is widely utilized as an analgesic and sedative agent, although it is considered a minimally potent inhalational anesthetic.2 Nitrous oxide is often recommended as a first-line option for children as it offers benefits such as amnesia and anxiolysis, making it an effective calming agent that raises the patient’s pain threshold and enhances the effectiveness of local anesthetics. Ultimately, N2O sedation helps ensure a more comfortable patient experience.3

The use of nitrous oxide has fluctuated over time. Around 150 years ago, it was widely utilized as an anesthetic but later fell out of favor. Today, while its use in general anesthesiology departments is declining, it is experiencing renewed popularity in dentistry, emergency medicine, and outpatient settings. Once a recreational drug favored by the elite, nitrous oxide has re-emerged in modern society, particularly among young people, as a recreational substance abused in canister form.2

Indications

Dental Anxiety

The prevalence of dental anxiety ranges from 5% to more than 24%, and it is particularly common in children.4 Because patients’ avoidance of dental treatment is a major barrier to oral health, behavioral management is a key issue.1 While many dental anxiety patients may be managed with nonpharmacological solutions, numerous cases require sedative interventions for successful dental treatment. Nitrous oxide sedation is associated with high patient compliance, ease of use, and a substantial history of efficacy and safety. Conscious sedation with nitrous oxide is successful in over 90% of cases involving anxious children.5 Despite these advantages, N2O is relatively underutilized in dental practice, which may be due to inadequate educational programs and a lack of confidence among dental practitioners in its capabilities.3

Dental anxiety negatively affects not only dental treatments in terms of patient compliance, but also other factors such as the success rate of local anesthetic administration. As such, dental professionals should be well-versed in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of N2O, as well as its administration, adverse effects, and modern advancements.

Pain Relief

Nitrous oxide has been used for general anesthesia, dental anesthesia, and in treating severe pain, with its analgesic properties proving useful in emergency department settings. Ideal effects of N2O include relaxation, light-headedness, and warmth.2 Patients may experience circumoral numbness, euphoria, and decreased muscle tone, but little-to-no changes to normal respiration.6

A split-mouth study investigating the physiological stress markers associated with N2O-treated periodontal surgeries concluded that, as an adjunct to local anesthesia, nitrous oxide effectively reduces physiological stress during periodontal surgical procedures. By measuring blood pressure and serum cortisol levels, intraoperative stress was found to be significantly lower in patients treated with nitrous oxide.7

Pediatric Dentistry

Pediatric dentistry entails challenges regarding behavioral management in young patients. Therefore, nitrous oxide can prove useful in children older than 3 years who are comfortable with nasal breathing.8 Parents tend to prefer nitrous oxide over restraint or general anesthetic.9 Effective communication with and management of such patients are essential factors impacting treatment success, patient compliance, and satisfaction.3 In a 2024 study, N2O sedation exhibited a high treatment success rate of 70% and a patient cooperation level of 75%, values higher than with oral sedation.10 A 2021 study indicated similar effectiveness among N2O sedation, oral midazolam, and dexmedetomidine in moderate sedation for pediatric dental procedures.11

Adult Dentistry

While frequently used in pediatric dentistry, nitrous oxide administration is also successful in adult dental care. Routine dental examinations and restorative procedures such as temporary crown placement and prosthesis insertion can benefit from the use of N2O, as can other treatments, including endodontic, periodontal, and surgical procedures. Notably, nitrous oxide minimizes gag reflex and increases comfort when using intraoral films and sensors during oral radiology in patients with specific anatomical restrictions such as exostoses and tori.3 Nitrous oxide is also a consideration for conscious sedation in elderly patients, who tend to be more anxious about dental treatments, although its effectiveness in patients with dementia is debated.12

Contraindications

While nitrous oxide is a safe and effective drug, it is contraindicated for certain patient populations. N2O sedation cannot be used for the behavioral management of a defiant child with minimal compliance and poor communication, as such patients are unable to accept the nasal mask required for N2O administration.1 Conditions that cause nasal blockage like the common cold, upper respiratory infections, bronchitis, allergies, and hay fever are contraindications for nitrous oxide administration, as they may prevent patients, especially children, from inhaling it effectively.4 N2O also should not be used in patients with significant respiratory diseases.2

Nitrogen, which makes up the majority of the Earth’s atmosphere, has a blood–gas partition coefficient 34 times smaller than that of N2O.13 This means that inhaled N2O diffuses out of blood into air-filled cavities 34 times faster than nitrogen can exit, leading to increased pressure and volume expansion.7 Thus, patients with conditions such as pneumothorax are contraindicated for care. Nitrous oxide can also increase the size of air emboli in the blood; therefore, its use is avoided in neurosurgery and cardiothoracic surgery, where air emboli are common.13 For the same reason, administering N2O to a child with a middle ear infection can increase middle ear pressure and potentially cause a painful eardrum rupture. In patients with bowel obstruction, N2O can cause gas expansion, leading to serious complications.

Nitrous oxide is contraindicated in patients diagnosed with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).11 These patients have impaired central hypercapnic centers and rely primarily on low oxygen levels, detected by peripheral hypoxemic centers, to regulate respiration.4 As noted earlier, N2O depresses these peripheral hypoxemic centers. Combined with the co-administration of oxygen, this could lead to dangerously low respiratory rates in these patients.3

Additionally, patients with nasopharyngeal obstruction, closed tissue spaces, and claustrophobia and those who have undergone vitreoretinal surgery within the past 3 months are contraindicated for care.14 Patients who have recently had retinal surgery may have trapped intraocular gas that could expand during N2O sedation, leading to intraocular hypertension and potentially irreversible vision loss.1 Caution should also be exercised with patients undergoing bleomycin chemotherapy, as the high oxygen administration with nitrous oxide shortens the half-life of bleomycin and could cause pulmonary fibrosis. These patients are contraindicated for N2O sedation for up to 1 year after bleomycin treatment.15

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry does not recommend the use of nitrous oxide within the first trimester of pregnancy and considers it a relative contraindication.9 Ideally, its administration should be limited to the second or third trimesters, used for less than 30 minutes, and given with at least 50% oxygen.1

Pharmacology

Chemical Structure and Properties

Nitrous oxide is a general anesthetic gas with no antigenic properties and a molecular weight of 44.013 g/mol. No stereoisomers of the compound have been identified. While nonflammable, it supports combustion, making it a potential fire hazard in dental settings. Nitrous oxide is present in minimal quantities in the atmosphere at 6 parts per million (ppm); however, it has been implicated in its contribution to the greenhouse effect.14

Commercial Preparation

In the preparation of nitrous oxide, ammonium nitrate crystals are heated commercially to a temperature of 245°C to 270°C, producing water as a side product. Several other compounds of minimal significance are formed, including ammonia, nitric acid, nitrogen, nitric oxide, and nitrogen dioxide.1 The gases are purified, compressed, dried, and evaporated before being stored in compressed gas cylinders.13

Physical Properties

Nitrous oxide has a melting point of -90.83°C and a boiling point of -88.57°C, making it a gas at room temperature.13 With a specific gravity of 1.53, nitrous oxide is heavier than air and is stored in cylinders under pressure, maintaining a liquid–gas equilibrium inside the cylinder. A full N2O tank contains approximately 95% liquid nitrous oxide and 5% vapor, pressurized at 750 pounds per square inch, and the compound remains in this state until less than 20% of the gas remains. Therefore, the pressure gauge is not a reliable indicator of the amount of nitrous oxide left, unlike oxygen tanks, where the pressure gauge accurately reflects the remaining volume. For this reason, it is recommended to always have a spare N2O tank available in the dental office.3

Pharmacokinetics

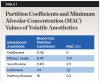

Because of its low solubility in blood (blood–gas partition coefficient = 0.47), nitrous oxide is rapidly absorbed via inhalation.1 Compared to other volatile anesthetics,16 N2O remains one of the quickest onset agents (Table 1). This partition coefficient represents the ratio of the amount of an agent in blood to the amount in gas when at equilibrium. The more soluble an agent is in blood, the longer it takes to raise the partial pressure of the agent, leading to a slower onset of anesthesia. Since nitrous oxide is poorly soluble in both adipose tissue and blood, with no binding to blood constituents, it has a rapid onset (15 to 30 seconds) and offset (10 to 15 minutes). It is absorbed through the lungs via diffusion and may induce the second-gas effect due to its rapid movement across the alveolar basement membrane, increasing the uptake of a second, slower gas. This rapid exit leads to an increased concentration of remaining alveolar gases, which accelerates the uptake of N2O into the bloodstream.

Nitrous oxide is not metabolized and is eliminated largely unchanged through exhalation.14 Less than 0.004% of N2O undergoes biotransformation via reductive metabolism in the gastrointestinal tract.3 It acquires its peak and plateau within minutes in vessel-rich groups such as the lungs and blood.2 Because of this property, a patient usually may be discharged home alone without a chaperone, whereas other general anesthetics typically require accompaniment from the hospital.3

The term minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) refers to the amount of anesthetic administered to incite an effect in 50% of individuals.14 With a MAC value of 104%, nitrous oxide’s potency as a volatile anesthetic agent is relatively low, making it ineffective as a sole agent for general anesthesia.1 As a result, nitrous oxide is often used in combination with more potent inhalational anesthetics, such as sevoflurane. Therefore, while N2O is classified as a weak inhalational anesthetic, it provides effective analgesic properties. Reversal of its effects may occur at the end of anesthesia, as N2O rapidly enters the alveoli, potentially leading to oxygen dilution and resulting in diffusion hypoxia.

Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacodynamics refer to how a drug, in this case nitrous oxide, interacts with the body to produce its effects, such as sedation, analgesia, and anesthesia. Current research provides more evidence into the analgesic mechanisms of nitrous oxide than its anxiolytic (anti-anxiety) and anesthetic mechanisms, which remain less understood (as discussed in the “Mechanism of Action” section below).

Research indicates that nitrous oxide produces analgesia by activating opioid receptors and releasing endogenous opioid peptides, typically achieved at lower concentrations of N2O (20% to 50%). N2O also induces sedation by modulating gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, the primary inhibitory neurotransmitters in the brain. By enhancing GABA activity, N2O exerts a depressant effect on the central nervous system, causing relaxation, reduced anxiety, and a sense of euphoria, often referred to as the “laughing gas” effect. Nitrous oxide also possesses anxiolytic properties, making it effective for calming patients during dental and medical procedures. This is partly due to its modulation of GABA receptors and its effects on other inhibitory pathways in the brain.

At lower doses, nitrous oxide provides sedation and analgesia and is administered at concentrations ranging from 20% to 50% for conscious sedation.2 However, its effects on the cardiovascular and respiratory systems are important to note when evaluating dental patients for care.

Nitrous oxide acts as a weak myocardial depressant and mild sympathomimetic, but it has a negligible impact on the cardiovascular system in healthy patients.14 Conflicting studies on the effects of N2O on myocardial infarction and mortality emerged in 2010, suggesting the avoidance of concentrations above 50%. However, a 2015 study confirmed the long-term safety of N2O administration in non-cardiac surgical patients with known or suspected cardiovascular disease.17

Nitrous oxide is a mild respiratory depressant and can potentiate the effects of other agents such as opioids, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines.8 It causes a dose-dependent reduction in tidal volume, with a reflexive increase in respiratory rate. Overall, its impact on respiration is minimal. N2O also depresses the central hypercapnic response and peripheral hypoxemic centers responsible for detecting changes in carbon dioxide levels.

Mechanism of Action: A Debated Topic

Having multiple mechanisms of action, studies have shed light on nitrous oxide’s analgesic, anxiolytic, and amnesic mechanisms.13,15 Research suggests that its analgesic effects are mediated through opioid pathways, while its anxiolytic and analgesic effects may mimic those of benzodiazepines, possibly by acting on specific subunits of the GABA type A (GABAᴀ) receptor. Similarly, N2O’s anesthetic effects are thought to involve interactions with GABAᴀ receptors, as well as potential action on N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors.1 N2O functions as an antagonist of NMDA receptors, which play a key role in pain transmission and consciousness. By inhibiting these receptors, N2O reduces pain sensation, contributing to its anesthetic properties.

Research also indicates that nitrous oxide stimulates the release of opioid peptides in the brainstem, activating descending noradrenergic neurons that modulate nociceptive processing in the spinal cord.18 This modulation helps to reduce pain perception. While the role of opioid receptors is not entirely consistent in the literature, some studies suggest the involvement of kappa (κ) and mu (μ) opioid receptors in inducing analgesia. In mouse studies, pharmacological blockage of κ-opioid receptors has been shown to block the effects of nitrous oxide, while blocking μ-opioid receptors produced inconsistent results.19

Another proposed mechanism involves the inhibition of NMDA receptors.20 A 50% concentration of N2O has been shown to block both NMDA and AMPA glutaminergic receptors in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, an area known to be involved in pain processing, suggesting the potential involvement of glutamate in N2O’s analgesic effects. Additionally, various receptor-effector mechanisms—including dopamine receptors, alpha-2 adrenoceptors, benzodiazepine receptors, and NMDA receptors—appear to play a role, although the exact interaction between these mechanisms remains unclear.

Adverse Effects

Nitrous oxide oversedation refers to the condition in which a patient is administered an excessive concentration of N2O, leading to extreme sedation or unintended side effects beyond the desired levels of conscious sedation.8 This can occur when N2O is given at concentrations above recommended levels or for longer durations than necessary. Symptoms of oversedation include altered hearing, visual disturbances, sleepiness, sweating, or other signs of discomfort (Table 2). Reducing the N2O levels by 5% has been recommended when any signs of oversedation are noticed.

While several adverse effects of nitrous oxide sedation, as described below, are possible, it is important to note that N2O administration under conditions stated in various guidelines is a safe technique. An evaluation of nearly 36,000 cases of 50% N2O sedation revealed only 0.03% serious adverse events, with 0.5% to 1.2% being nausea and vomiting.21 Clinicians should conduct a thorough review of the advantages and disadvantages of nitrous oxide use for each patient before treatment (Table 3).

Nausea and vomiting: The most common adverse effect of nitrous oxide is vomiting, with preoperative fasting found as a correlation. The rate of vomiting in patients who ate a light snack 2 hours before administration was lower than what was found in other studies.22 However, greasy, fatty meals are not recommended before the administration of N2O.

Tension in air-filled spaces: Nitrous oxide is 34 times as soluble as nitrogen, the main constituent of air at 79%; thus, there could be an increase in volume and pressure in sites where air may be trapped.9 The increased pressure may result in tension in air-filled spaces, which can lead to middle ear disease, pneumothorax, and obstructed bowel. Special care must be taken for patients who have undergone vitreoretinal surgery. The intraocular gases used for such a surgery are highly insoluble; therefore, the increased pressure around the optic nerve places additional pressure around the blood vessels, resulting in potential infarction and blindness.8

Diffusion hypoxia: Due to the dose of nitrous oxide, there is relative hypoxia. It is recommended that all cases employing N2O end the treatment with 100% pure oxygen to prevent such an event. Nitrous oxide–associated deaths are often due to asphyxiation and the prevention of adequate inhalation of oxygen.14

Toxicity: Nitrous oxide toxicity has been a subject of controversy and debate. One of the first major studies on this topic, conducted in 1975, investigated the effects of vapor exposure on medical anesthesiologists. It reported increased health problems, including spontaneous abortions.23 The study suggested that N2O exposure could suppress deoxyuridine, leading to altered DNA at long-term exposure levels of 1,800 ppm.13 However, the study emphasized that the risk of toxicity primarily affects the healthcare staff administering N2O, who are exposed to the gas consistently, rather than the patients. Clinically significant effects may arise only if N2O is administered continuously for more than 6 hours.

Although nitrous oxide is chemically inert, it can still cause the irreversible oxidation of cobalt ions in vitamin B12 (cobalamin), rendering its coenzyme inactive.14 This is widely considered the primary mechanism behind the neurological and hematological toxicity associated with nitrous oxide. Cobalamin plays a crucial role in the formation of the myelin sheath and red blood cells. Chronic exposure or repeated use in susceptible individuals can lead to cobalamin deficiency, which may result in peripheral neuropathy, spinal cord degeneration, and impaired red blood cell production. Additionally, there is a risk of toxicity from N2O abuse, which can manifest as paresthesia, numbness, muscle weakness, impotence in males, and Lhermitte’s sign (an electrical sensation down the spine). Cessation of nitrous oxide, along with B12 supplementation, can potentially result in the reversal of symptoms.

Safety among personnel: While there is conflicting evidence on N2O toxicity, precautions must be taken to minimize exposure. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health recommends keeping nitrous oxide concentrations below 25 ppm, based on older studies that showed negative effects on psychomotor performance at 50 ppm.24 To ensure safety, a scavenger system must be employed, and exhaust systems should be properly installed to maximize air circulation. Regular inspections for leaks are crucial. Additionally, the use of a nasal hood, rubber dam, and high-speed suction can help further prevent N2O exposure.

Abuse and potentiation of other sedatives: Nitrous oxide can potentiate the effects of other sedatives, which can occur either intentionally or unintentionally. This risk is particularly concerning in patients with a history of substance abuse, including alcohol. Special care should be taken in these cases. Deep sedation increases the risk of aspiration, especially if the patient has consumed food recently, potentially leading to fatal consequences.25 Additionally, due to the potential for dysphoria and disinhibited reactions, strict guidelines demand that patients undergoing nitrous oxide sedation have a secondary attendant, in addition to the primary dental practitioner, to ensure safety.26

Nitrous Oxide Emergencies

Although rare, possible emergencies involving nitrous oxide include overdose, crossed lines, and airway fire. Training in the appropriate emergency response is mandatory for providers of analgesic agents.

Overdose: Due to patient variability, in certain, more susceptible individuals, overdose of nitrous oxide can lead to inadvertent general anesthesia. Patients become unresponsive to physical stimulation and verbal commands. In such cases, it is important to monitor their airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC) and immediately shut off the N2O and increase the flow of oxygen. Laryngospasm, a spasm of the vocal cords, has also been reported with the administration of N2O.22 As a condition that only occurs in deep sedation, this symptom of overdose would render the patient unable to speak or breathe. Because of patient variability, care must be taken to observe and titrate the concentration of nitrous oxide.6

Crossed lines: On rare occasions there may be a potential for gas lines of oxygen and nitrous oxide to be crossed, resulting in 100% N2O inadvertently being administered instead of oxygen.27 Such a mishap may occur due to new systems being in place or recent renovations in the office. This scenario emphasizes the importance of a proper machine check before anesthetic administration.27 To manage this situation, the same steps as described for an overdose should take place.

Airway fire emergency, a rare complication: Rarely, a patient’s airway may become involved in a surgical fire, which may include a fire in the breathing circuit. Airway fire constitutes 21% of all surgical fires and requires three components to ignite: an oxidizer such as oxygen, an ignition source like electrosurgery units, and fuel such as cotton rolls.28 To prevent such an event, intraoral high-speed suctioning is indicated during the procedure to prevent oxygen pooling. The flow of oxygen is also to be stopped 1 minute prior to the use of an ignition source. Fuels should also be moistened before use. In the event of this emergency, the burning material should first be removed and the fire extinguished by smothering it or pouring water, the gas stopped, and the patient managed based on the injuries sustained.28

Clinical Administration Techniques

Patient Selection and Preparation

Although nitrous oxide is deemed to be a universally accepted adjunct of treatment, a review of the patient’s medical history is essential when considering whether or not to use it, as mentioned previously (Table 4). Assessment of the patient should include previous allergies to medication, diseases, pregnancy status, and previous hospitalizations.

As previously noted, nitrous oxide is a behavior management tool, making it essential to assess a child’s anxiety or fear during the initial appointment and obtain informed consent. Parents should be reassured that the drug is commonly and safely used, with no lasting side effects. The patient’s record must document the indications for N2O sedation, including detailed notes on the concentration administered, monitored variables, procedure duration, post-treatment oxygenation, and any complications or absence thereof. A thorough medical history, including confirmation of no upper respiratory infections, is crucial to ensure the child can breathe through the nose.8

Crucial to successful nitrous oxide sedation is the patient’s acceptance of the nasal mask.29 It may be helpful to provide a mask for a child to take home and practice breathing through the nose. The mask should be appropriately sized, and various techniques, such as introducing the mask in a way suited to the child’s comprehension, using scented masks, or adding flavoring to create a pleasant smell, can improve cooperation.1

Before the patient enters the operatory, it is important to prepare equipment, and preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative vital signs must be recorded.30 While fasting is not required, it is recommended that patients consume a light meal no later than 2 hours prior to treatment.1 Patients should be informed of fasting instructions before the first nitrous oxide appointment.14

Induction

The incremental induction technique is often used for the administration of nitrous oxide for new patients.30 Gas flow should match the tidal volume of the patient, which is the amount of air movement out of the lungs during quiet breathing.1 A flow rate of 5 to 6 L/min on average for most patients is adequate. For the first 1 to 2 minutes 100% oxygen should be administered, and the patient should be reminded to breathe through the nose, with a nasal hood in place and the reservoir bag being observed. Ideally, the reservoir bag should fill smoothly without over- or underinflation, pulsating gently with each breath.31 The flow rate can be adjusted as needed.

Administration of N2O should start at 20% after the initial 100% oxygen administration, keeping in mind that many patients feel no effect at 20%; concentration should not exceed 50%, as this can cause very deep sedation.30 To ensure ideal sedation, talking and mouth breathing should be minimized. If the initial concentration is insufficient, a 5% incremental increase technique should be employed, allowing 1 to 2 minutes of observation and stopping when satisfactory symptoms appear.30,32 Most patients should have satisfactory symptoms within 50%. Re-examination of proper mask fit and leakage is indicated if no effect is observed at this level. Once the patient is appropriately managed, dentistry can begin with consistent observation of signs of minimal or moderate sedation (Table 2). Concentrations may be diminished for procedures that are easier to tolerate and augmented for more stimulating procedures, such as periodontal surgery or local anesthetic administration.

When treatment is complete, the flow of nitrous oxide should be terminated with 3 to 5 minutes of 100% oxygen administration or until the patient reverts to pretreatment status.5,33 Discharge criteria of stable vital signs, progressive awakening, easy arousal, and an ambulatory patient should be observed before allowing the patient to leave the office unescorted. The dental healthcare professional should record the percentage of nitrous oxide used, total liter flow, and duration in the patient’s chart for future reference. With this information, future appointments can begin at the percentage of N2O used at the previous appointment.

Conclusion

Nitrous oxide remains a widely used inhalation sedation agent in contemporary dental practice that is particularly valued for its rapid onset, ease of titration, and favorable safety profile. It is integral in managing dental anxiety and facilitating treatment across a wide range of patient groups, including pediatric, anxious, and medically compromised individuals. Considering ongoing developments in sedation protocols and patient safety standards, this review highlights current evidence regarding the pharmacology, clinical indications, and risk factors associated with N2O administration. Appropriate patient assessment, clinician training, and adherence to regulatory guidance is emphasized.

Dental practitioners are encouraged to remain engaged with continuing professional development and foster collaborative working relationships with colleagues in sedation and anesthesia. Staying abreast of advances in technology and clinical guidelines is essential to ensuring high standards of patient care, safety, and informed clinical decision-making.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Lynda Jiayi Wo, BSc

Fourth-Year Dental Student, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Aviv Ouanounou, BSc, MSc, DDS

Associate Professor, Department of Clinical Sciences, Pharmacology and Preventive Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Fellow, International College of Dentists; Fellow, American College of Dentists; Fellow, International Congress of Oral Implantologists

Queries to the author regarding this course may be submitted to authorqueries@conexiant.com.

REFERENCES

1. Emmanouil D. The pharmacology, physiology and clinical application in dentistry of nitrous oxide. In: Mason KP, ed. Pediatric Sedation Outside of the Operating Room. 3rd ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021:199-210.

2. Li X, Liu Y, Li C, Wang J. Sedative and adverse effect comparison between oral midazolam and nitrous oxide inhalation in tooth extraction: a meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23(1):307.

3. Mukundan D, Gurunathan D. Effectiveness of nitrous oxide sedation on child’s anxiety and parent perception during inferior alveolar nerve block: a randomized controlled trial. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e48646.

4. Popescu SM, Dascălu IT, Scrieciu M, et al. Dental anxiety and its association with behavioral factors in children. Curr Health Sci J. 2014;40(4):261-264.

5. Vanhee T, Lachiri F, Van Den Steen E, et al. Child behaviour during dental care under nitrous oxide sedation: a cohort study using two different gas distribution systems. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2021;22(3):409-415.

6. Valtonen P, Markkanen S, Järventausta K, et al. More than just joy: a qualitative analysis of participant experiences during nitrous oxide sedation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2024;68(7):906-912.

7. Sandhu G, Khinda PK, Gill AS, et al. Comparative evaluation of stress levels before, during, and after periodontal surgical procedures with and without nitrous oxide-oxygen inhalation sedation. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2017;21(1):21-26.

8. Ashley P, Anand P, Andersson K. Best clinical practice guidance for conscious sedation of children undergoing dental treatment: an EAPD policy document. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2021;22(6):989-1002.

9. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Use of nitrous oxide for pediatric dental patients. In: The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, IL: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2024:394-401.

10. Kumar Verma R, Sindgi R, Gavarraju DN, et al. Effectiveness of different behavior management techniques in pediatric dentistry. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2024;16(suppl 3):S2434-S2436.

11. Unkel JH, Berry EJ, Ko BL, et al. Effectiveness of intranasal dexmedetomidine with nitrous oxide compared to other pediatric dental sedation drug regimens. Pediatr Dent. 2021;43(6):457-462.

12. Nicolas E, Lassauzay C. Interest of 50% nitrous oxide and oxygen premix sedation in gerodontology. Clin Interv Aging. 2009;4:67-72.

13. Temple E, Wiles M. Inhalational anaesthetic agents. Anaesth Intensive Care Med. 2019;20(2):109-117.

14. Gupta N, Gupta A, Narayanan MRV. Current status of nitrous oxide use in pediatric patients. World J Clin Pediatr. 2022;11(2):93-104.

15. Iyer AK, Ramesh V, Castro CA, et al. Nitric oxide mediates bleomycin-induced angiogenesis and pulmonary fibrosis via regulation of VEGF. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116(11):2484-2493.

16. Esper T, Wehner M, Meinecke CD, Rueffert H. Blood/gas partition coefficients for isoflurane, sevoflurane, and desflurane in a clinically relevant patient population. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(1):45-50.

17. Leslie K, Myles PS, Kasza J, et al. Nitrous oxide and serious long-term morbidity and mortality in the Evaluation of Nitrous Oxide in the Gas Mixture for Anaesthesia (ENIGMA)-II trial. Anesthesiology. 2015;123(6):1267-1280.

18. Fujinaga M, Doone R, Davies MF, Maze M. Nitrous oxide lacks the antinociceptive effect on the tail flick test in newborn rats. Anesth Analg. 2000;91(1):6-10.

19. Sanders RD, Weimann J, Maze M. Biologic effects of nitrous oxide: a mechanistic and toxicologic review. Anesthesiology. 2008;109(4):707-722.

20. Georgiev SK, Kohno T, Ikoma M, et al. Nitrous oxide inhibits glutamatergic transmission in spinal dorsal horn neurons. Pain. 2008;134(1-2):24-31.

21. Onody P, Gil P, Hennequin M. Safety of inhalation of a 50% nitrous oxide/oxygen premix: a prospective survey of 35,942 administrations. Drug Saf. 2006;29(7):633-640.

22. Chi SI. Complications caused by nitrous oxide in dental sedation. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2018;18(2):71-78.

23. Cohen EN, Brown BW Jr, Bruce DL, et al. A survey of anesthetic health hazards among dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 1975;90(6):1291-1296.

24. Bruce DL, Bach MJ, Arbit J. Trace anesthetic effects on perceptual, cognitive, and motor skills. Anesthesiology. 1974;40(5):453-458.

25. Parker JD. Pulmonary aspiration during procedural sedation for colonoscopy resulting from positional change managed without oral endotracheal intubation. JA Clin Rep. 2020;6(1):53.

26. Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario. Standard of practice: use of sedation and general anesthesia in dental practice. 2018. https://www.rcdso.org/en-ca/permits-and-renewals/sedation-and-anesthesia. Accessed November 13, 2025.

27. Ellett AE, Shields JC, Ifune C, et al. A near miss: a nitrous oxide-carbon dioxide mix-up despite current safety standards. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(6):1429-1431.

28. Balduyeu P, Loeb RG. Airway fire. In: Berkow LC, ed. Emergency Anesthesia Procedures. New York: Oxford University Press; 2024:3-8.

29. Mourad MS, Santamaria RM, Splieth CH, et al. Impact of operators’ experience and patients’ age on the success of nitrous oxide sedation for dental treatment in children. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2022;23(3):183-188.

30. Khinda V, Rao D, Sodhi SPS. Nitrous oxide inhalation sedation rapid analgesia in dentistry: an overview of technique, objectives, indications, advantages, monitoring, and safety profile. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2023;16(1):131-138.

31. Kharouba J, Somri M, Hadjittofi C, et al. Effectiveness and safety of nitrous oxide as a sedative agent at 60% and 70% compared to 50% concentration in pediatric dentistry setting. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2020;44(1):60-65.

32. Grisolia BM, Dos Santos APP, Dhyppolito IM, et al. Prevalence of dental anxiety in children and adolescents globally: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2021;31(2):168-183.

33. Yee R, Wong D, Chay PL, et al. Nitrous oxide inhalation sedation in dentistry: an overview of its applications and safety profile. Singapore Dent J. 2019;39(1):11-19.