You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

The attached gingiva (AG), also referred to as attached mucosa, immobile mucosa, attached keratinized tissue, marginal attached tissue, etc, is a crucial component of periodontal health. The AG is firmly bound to the underlying alveolar bone via the periosteum and teeth through attachment apparatuses. It is distinguished from the free gingiva, which is not attached to the tooth and forms the outer boundary of the gingival sulcus.1 The width of the AG is measured from the mucogingival junction (MGJ) to the projection on the external surface of the bottom of the gingival sulcus or periodontal pocket.1,2 The histological components of the AG, including the epithelium, connective tissue, basement membrane, and various cellular elements, work together to provide structural integrity, protective functions, and a dynamic response to environmental challenges.3

Over the years, the dental profession has seen a progressive evolution in the understanding of the AG and its crucial role in periodontal health. In the early 20th century, research that was focused on understanding the structure and function of the gingiva led to the identification of different gingival zones. Orban and Sicher’s fundamental research in the 1940s and 1950s offered a comprehensive anatomical and histological insight into the gingiva.4 During the 1970s, Lang and Löe’s research emphasized the importance of AG width in maintaining periodontal health, influencing contemporary periodontal therapy and diagnosis.5

Importance of Attached Gingiva

The width of the AG is crucial for oral health for several reasons. First, it provides protection against mechanical stress encountered during mastication and oral hygiene practices. Additionally, its strong attachment to the underlying structures helps in distributing forces, reducing the risk of tissue damage. Further, the AG acts as a barrier to pathogens, preventing the ingress of bacteria and other harmful agents into the periodontal tissues. This barrier function is essential in inhibiting the onset and progression of periodontal diseases. Moreover, an adequate width of AG can help facilitate effective oral hygiene, as areas with insufficient AG may be prone to discomfort during brushing, resulting in suboptimal oral hygiene and increased plaque accumulation.

In periodontal therapy and restorative dentistry, maintaining or increasing the width of AG is crucial for achieving optimal esthetics and function, especially in labial/buccal areas. Procedures such as gingival grafting are often used to enhance the width of AG in areas with deficiencies.6 Gingival sensitivity and a propensity for marginal tissue recession have been associated with thinner phenotypes.

Over the years, clinicians and researchers have learned explicitly through the discipline of dental implantology the importance of attached tissue around the implant—not only its width but also its breadth, on both the buccal and lingual aspects. Research has also indicated long-term stability of the alveolar crest and resistance to its resorption can be related to the presence of adequate attached tissue.7

Assessing the width of AG is a critical part of periodontal examination and treatment planning. Clinicians use various methods, such as visual evaluation, tension tests, the rolling probe, and histochemical staining with Lugol’s iodine, to delineate the MGJ. It is advisable to use two or more methods for this assessment.8-10

The width of AG varies significantly across the different regions of the mouth.9 This variability is influenced by several factors, including anatomical location, individual genetics, developmental factors, functional needs, and oral habits. Understanding these variations is crucial for effective periodontal assessment and treatment planning. The width of AG ranges from 3.5 mm to 4.5 mm in the maxillary anterior region and from 3.3 mm to 3.9 mm in the mandibular anterior region; in the maxillary posterior region, AG width ranges from 1.9 mm to 3 mm, and in the mandibular posterior region it ranges from 1.8 mm to 2.1 mm.6

Despite extensive research having been done on the buccal AG, there is a significant lacuna for the lingual AG. The only available study in the international databases is by Voigt et al in 1978,11 which highlighted the variations in the width of the lingual AG, noting that the greatest average width was found on the lingual aspect of the first and second mandibular molars, with decreasing widths observed in the bicuspids, third molars, and culminating with the least amounts on the central incisors, lateral incisors, and cuspids. That study, however, is more than four decades old, and there is a need for contemporary research to expedite understanding of lingual gingival anatomy, which has key implications for periodontal health, orthodontics, restorative dentistry, and implant dentistry.

The present study, therefore, aims to review the much-overlooked aspect of examination of the lingual AG and investigate its average apicocoronal width across various regions of the mandible.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional observational study analyzed the width of AG on lingual surfaces of mandibular teeth in periodontally healthy individuals. The study included 120 participants aged 18 to 30 years, of both male and female gender, with fully erupted teeth (excluding third molars) and intact periodontium. Eligible subjects had to meet the periodontal health criteria as presented in the 2017 Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions,12 exhibiting minimal clinical inflammation, no attachment loss, no more than the presence of physiological mobility of teeth, good gingival health, less than 10% bleeding on probing, and pocket depths of 3 mm or less. Exclusion criteria included individuals undergoing orthodontic treatment or having malpositioned teeth, periodontitis, systemic diseases affecting periodontal health, mucogingival deformities, physical or mental handicaps, tobacco use, or a history of periodontal surgery in the past 6 months.

Subjects meeting the selection criteria were enrolled in the study after receiving a clear explanation of the study in their preferred language. The width of keratinized gingiva (KG) was measured from the gingival margin to the MGJ using a UNC-15 periodontal probe, focusing on the mid-lingual area of all mandibular teeth.

The MGJ was delineated by the visual method and the roll method following clinical examination in dental chairs appropriately equipped. Visual assessment relies on identifying the color difference between the gingiva and alveolar mucosa. The mucosa beyond the MGJ typically appears darker red compared to the AG, helping to demarcate the MGJ. The rolling probe method entails pushing the neighboring alveolar mucosa coronally with the blunt end of a probe. It is a functional assessment method that aids in determining the boundary between gingiva and movable mucosa.10 The probing sulcus depth was subtracted from the measured KG width at the mid-lingual aspect of each tooth to determine the width of AG, and all fractional measurements were rounded off to the nearest whole number of millimeters (Figure 1 through Figure 3).

Statistical Data Analysis

The data from each subject was collected, and statistical analysis was done for all mandibular teeth to assess the width of the lingual AG. The analysis included calculating the mean, standard deviation, mode, and extreme measurements, encompassing both the lowest and highest readings. These metrics provided a comprehensive overview of the variation in gingival width across mandibular teeth. Additionally, descriptive statistics for male and female subjects were recorded.

Results

The study was performed in the Department of Periodontology at the Maharashtra Institute of Dental Sciences and Research, in Latur, Maharashtra, India, in May 2023. A total of 150 undergraduate and postgraduate students out of 565 students of the institute were initially selected using simple random sampling. After excluding 30 students because of various reasons (eg, subjects with orthodontic treatment, presence of high lingual freni, poor oral hygiene, gingival recession, teeth crowding, refusal to voluntarily participate, etc), 120 subjects were included in the study, and written consents were obtained.

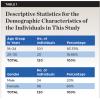

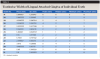

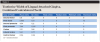

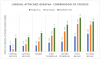

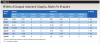

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the demographic characteristics of the participants: 83.33% of the study population were aged 18 to 24 years, while 16.66% were aged 25 to 30 years, and 20% of the participants were male while 80% were female, indicating a skewed distribution. Figure 4 through Figure 6 illustrate lingual AG of a representative male subject, and Figure 7 through Figure 9 depict that of a female subject. The mean, standard deviation, mode, median, and extremes for all the mandibular permanent teeth are recorded in Table 2. The extreme measurements were in the range of 0 mm to 10 mm, considering all teeth and subjects. The width of lingual AG varied with each tooth, with the mandibular first molar having the widest average width (6 mm ± 1.3 mm) followed closely by the second molar (5.8 mm ± 1.2 mm). The central incisors (0.5 mm ± 0.5 mm) showed the narrowest zone along with the highest maximum number of teeth without detectable AG (Table 3). The width of AG did not significantly differ between the sexes (Table 4). The overall indicative schematic of lingual AG is shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11.

Discussion

The authors evaluated 120 subjects to assess the presence and width of lingual AG, an important parameter for periodontal health. Surprisingly, there is a dearth of research on this topic, with only a detailed study by Voigt et al11 and a later study by Pardeshi et al13 in a non-academic journal. The limited visibility and accessibility of the lingual AG may contribute to challenges for clinicians in measuring its width. Patient concerns regarding this aspect have been scarcely documented and typically have not been included in comprehensive medical histories. While the esthetic and functional importance of the buccal side of AG is often prioritized, it is crucial to note that the stability of the investing and supporting tissues of teeth hinges on the health of the entire cohesive unit.

Although the male:female ratio in the present study was skewed, the nonsignificant differences in AG width may nullify the heterogeneity; nonetheless, the authors acknowledge that it is advisable to conduct a study with a comparable number of subjects. This study’s participants were in a developmentally mature age group in whom the traumatic effects of toothbrushing as well as prevalence of periodontal diseases usually is minimal. Like this study, Voigt et al also examined 120 subjects, and although their study consisted of all ages from 3 years and up it included 20 males and 20 females aged 15 to 35 years,11 which is in line with the present study. Their results for the 15–35 age range do not reflect the present study: central incisor 1.4 mm (their study) versus 0.54 mm (present study), lateral incisor 1.25 mm versus 1.62 mm, canine 1.35 mm versus 2.21 mm, first premolar 1.95 mm versus 3.44 mm, second premolar 2.15 mm versus 4.34 mm, first molar 3.3 mm versus 5.97 mm, and second molar 3.85 mm versus 5.8 mm. The differences in the width of lingual AG are quite significant and probably indicative of different target populations or limited sample size. Pardeshi et al evaluated 50 subjects in the age range of 18 to 30 years, and their findings were: central incisor 2.9 mm, lateral incisor 3.1 mm, canine 4 mm, first premolar 5.1 mm, second premolar 5.8 mm, first molar 7.3 mm, and second molar 6.5 mm,13 which are significantly higher than the present study. The present study results lie between these two studies and seem to be realistic for the sample size and age group (Figure 12).

Overall, these studies indicate that the lingual AG width increases in the posterior direction. The trend, however, is exactly the opposite for maxillary buccal AG as reported by Bowers,9 who in 1963 investigated the width of AG for the first time on North Americans at Ohio State University. He also reported that the width of mandibular buccal AG is narrowest at the canine–premolar region.

Voigt et al included six age groups: 3 to 5 (deciduous), 6 to 11 (mixed dentition), 9 to 14 (permanent dentition), 15 to 25, 26 to 35, and 36 years and older, with each group comprised of 10 males and 10 females.11 Similar to the present study, the authors reported no differences in male versus female width of lingual AG. For the latter three permanent dentition groups, the means for central incisor, lateral incisor, canine, first premolar, second premolar, first molar, and second molar were 1.4 mm, 1.3 mm, 1.4 mm, 2 mm, 2.5 mm, 4.7 mm, and 4.7 mm, respectively. The extreme values reported by Voigt et al were 1 mm and 8 mm, whereas for the present study these values were 0 mm and 10 mm. The more dispersed values in the present study may indicate population-wide differences.

Lang and Löe in 1972 also reported insignificant sex-related variations in the width of AG,5 similar to Voigt et al11 and the present study. These findings suggest that despite height and other morphological differences between males and females, on average the width of AG remains unchanged.

Although Shaju and Zade concluded that width of buccal AG varies with age, gender, and location in the mouth, much of the information was not detailed in their article.14 Those authors as well as Chandulal et al revealed that the overall mean width of buccal AG is wider in females (3.03 mm) compared to males (2.67 mm), but both studies reported exactly the same measurements and conducted their studies on a limited number of teeth.14,15

AG serves protective purposes for both natural teeth and dental implants, making its adequacy one of the most important aspects of the periodontium. Several clinical studies have highlighted the importance of AG around dental implants, particularly in relation to stability of hard and soft tissues.16 Maintaining keratinized and immobile mucosa around the implant is crucial to impeding the spread of inflammation from plaque and facilitating comfortable hygiene procedures.17 In an interventional animal trial, Warrer et al confirmed that the lack of AG at implant sites increases susceptibility to inflammation and bone loss.18 Chung et al also found similar results, especially for implants positioned in posterior sextants.19 It is well known in periodontal literature since Wennström and Lindhe’s study20 that gingiva with a narrow zone of attachment is more susceptible to inflammation compared to wider zones.

While much of the aforementioned research has focused on buccal AG, the problems associated with lingual AG are not uncommon; gingival recession, gingival and dentin hypersensitivity, and esthetic and functional issues have been reported. Goktas et al evaluated the biomechanical behavior of buccal and lingual AG and alveolar mucosa and reported the highest values of tensile strength, stiffness, steady modulus, and stress and strain amplitude for buccal AG.21

While the present study provides valuable data, its limitations must be acknowledged. The study’s cross-sectional design and relatively small sample size may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the methods used to measure the width of the AG, although standardized, may be subject to some degree of measurement error. The male-to-female ratio could be improved upon, and the study could be extended to wider age groups.

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, this study highlights significant variations in the width of lingual AG across different mandibular teeth and identical values for males and females. The authors’ findings reveal that the width of lingual AG increases from central incisor to second molar. The central incisors have the narrowest widths of lingual AG, while the first molars have the widest.

To confirm these results unambiguously and to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the lingual AG, further studies with larger sample sizes and diverse populations are needed. Future research should also explore the potential impact of various factors such as age, gender, tongue musculature, and oral habits on the width of the lingual AG. Additionally, longitudinal studies could provide insights into how the width of lingual AG changes over time as it is well known that the width of buccal AG increases with age.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Om Nemichand Baghele, MDS, MBA

Professor, Department of Periodontology, Maharashtra Institute of Dental Sciences and Research, Latur, Maharashtra, India; PhD Scholar, Mahatma Gandhi Misson’s Dental College and Hospital, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Vishnudas Dwarkadas Bhandari, MDS

Professor, Department of Periodontology, Maharashtra Institute of Dental Sciences and Research, Latur, Maharashtra, India

Nikita Vikasrao Palkar, MDS

Ex-Resident, Department of Periodontology, Maharashtra Institute of Dental Sciences and Research, Latur, Maharashtra, India; Private Practice, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Gauri Mahesh Ugale, MDS

Professor, Department of Periodontology, Maharashtra Institute of Dental Sciences and Research, Latur, Maharashtra, India

Queries to the author regarding this course may be submitted to authorqueries@conexiant.com.

REFERENCES

1. Ainamo J, Löe H. Anatomical characteristics of gingiva. A clinical and microscopic study of the free and attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1966;37(1):5-13.

2. Bhatia G, Kumar A, Khatri M, et al. Assessment of the width of attached gingiva using different methods in various age groups: a clinical study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015;19(2):199-202.

3. Oh SL. Attached gingiva: histology and surgical augmentation. Gen Dent. 2009;57(4):381-385.

4. Orban B, Sicher H. Oral Histology and Embryology. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company; 1944.

5. Lang NP, Löe H. The relationship between the width of keratinized gingiva and gingival health. J Periodontol. 1972;43(10):623-627.

6. Newman MG, Takei H, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA. Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences Division; 2011:513-562.

7. Schwarz F, Derks J, Monje A, Wang HL. Peri‐implantitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(suppl 20):S246-S266.

8. Guglielmoni P, Promsudthi A, Tatakis DN, Trombelli L. Intra- and inter-examiner reproducibility in keratinized tissue width assessment with 3 methods for mucogingival junction determination. J Periodontol. 2001;72(2):134-139.

9. Bowers GM. A study of the width of attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1963;34(3):201-209.

10. Baghele ON, Bezalwar KV. A study to evaluate the prevalence of teeth without clinically detectable mucogingival junction. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2022;26(2):162-168.

11. Voigt JP, Goran ML, Flesher RM. The width of lingual mandibular attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1978;49(2):77-80.

12. Chapple ILC, Mealey BL, Van Dyke TE, et al. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri‐Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(suppl 20):S68-S77.

13. Pardeshi KV, Agrawal AA, Mirchandani NM, Kohale BR. An epidemiologic study to determine the width of lingual attached gingiva, presence of lingual recession and patient’s awareness. Int J Dent Health Sci. 2016;3(1):30-39.

14. Shaju JP, Zade RM. Width of attached gingiva in an Indian population: a descriptive study. Bangladesh J Med Sci. 2009;8(3):64-67.

15. Chandulal D, Jayshri W, Bansal N. Measurement of the width of attached gingiva in an Indian subpopulation. Indian J Dent Adv. 2016;8(1):14-17.

16. Ramanauskaite A, Schwarz F, Sader R. Influence of width of keratinized tissue on the prevalence of peri-implant diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2022;33(suppl 23):8-31.

17. Satpathy A, Grover V, Kumar A, et al. Indian Society of Periodontology good clinical practice recommendations for peri-implant care. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2024;28(1):6-31.

18. Warrer K, Buser D, Lang NP, Karring T. Plaque-induced peri-implantitis in the presence or absence of keratinized mucosa. An experimental study in monkeys. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1995;6(3):131-138.

19. Chung DM, Oh TJ, Shotwell JL, et al. Significance of keratinized mucosa in maintenance of dental implants with different surfaces. J Periodontol. 2006;77(8):1410-1420.

20. Wennström J, Lindhe J. Role of attached gingiva for maintenance of periodontal health. Healing following excisional and grafting procedures in dogs. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10(2):206-221.

21. Goktas S, Dmytryk JJ, McFetridge PS. Biomechanical behavior of oral soft tissues. J Periodontol. 2011;82(8):1178-1186.