You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

Caries prevention involves strategies to reduce the risk of developing new carious lesions, while remineralization treatments arrest or repair existing lesions. Rather than an isolated event, caries is a process where there is more demineralization than remineralization of tooth structure over time. Further, carious lesions exist along a continuum from initial demineralization to subsurface lesions to eventual surface cavitation. Therefore, some overlap exists in the strategies used for prevention and remineralization. This review article addresses the current evidence and strategies for both.

Fluoride for Caries Prevention

Fluoride helps to prevent caries by increasing enamel resistance to mineral loss in acidic conditions. Enamel is composed of hydroxyapatite mineral, Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2. In the presence of fluoride, normal remineralization may result in uptake of fluoride ions to be incorporated into fluorapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)(2-x)F) within dental hard tissues. The replacement of hydroxyl groups (-OH) in hydroxyapatite by smaller fluoride ions in fluorapatite leads to a more compact crystalline arrangement. These more compact crystals are more resistant to demineralization in low pH environments. The electrostatic forces between the oppositely charged ions is stronger at a shorter distance, and therefore the more compact fluorapatite crystals have higher forces of attraction between ions and lower solubility.1

The benefit of fluoride was first discovered in the early 1900s by the caries resistance of a population receiving naturally occurring fluoride from ground water in Colorado Springs, Colorado. The evidence for the intentional use of fluoride to prevent caries dates to the fluoridation of drinking water in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in the 1940s. This public health initiative resulted in a significant reduction in the number of decayed, missing, or filled teeth (DMFT) in children 10 years after fluoride was added to the municipal water supply.2 Since the implementation of community water fluoridation (CWF), its benefit has been questioned due to the widespread use of fluoride in oral health products, which started around 1975. An updated Cochrane review recently reported that the improvement in DMFT after CWF implementation in studies after 1975 was not as great as the improvements in studies prior to 1975.3 Presumably, CWF should still benefit those who do not have access to fluoride in oral health products; however, the review found insufficient evidence to suggest that cessation of CWF increased disparities of caries rates between socioeconomic groups.3 Regardless, the results suggest that CWF has public health benefit despite the lessened effect following widespread use of fluoride toothpaste.

Fluoride is present in over-the-counter toothpaste at 1,000 parts per million (ppm) and prescription toothpaste at 5,000 ppm as compared to drinking water at 0.7 ppm to 1 ppm. The use of high-concentration fluoride toothpaste leads to increased salivary fluoride concentrations hours after brushing.4,5 Aside from fluoride in toothpaste, it is also present in other prevention products, such as mouthrinse, varnish, and fluoride trays.

Fluoride may be added to over-the-counter mouthrinse at 0.02% to 0.05% sodium fluoride (92 ppm to 230 ppm) or to prescription mouthrinse at 0.2% sodium fluoride (900 ppm). A Cochrane review of fluoride mouthrinses stated that there is a 23% reduction in DMFT when using fluoride-containing mouthrinses (stating no difference in effects between 0.05% and 0.2% sodium fluoride versions). The review suggested that fluoride mouthrinse has benefit even if the patient had background exposure to fluoride (eg, toothpaste). The authors, however, noted that this claim is not based on studies that compared the use of fluoride toothpaste and mouthrinse in the same study, and that classifying studies in which patients had background fluoride exposure was often based on marketplace assumptions.6 Clinical trials that examined 0.05% sodium fluoride mouthrinse and toothpaste in the same study reported that there was no additional benefit in preventing caries if fluoride mouthrinse was used in conjunction with fluoride toothpaste. However, fluoride mouthrinse did reduce the incidence of caries if fluoride toothpaste was not used.7,8 Therefore, use of fluoride mouthrinse may be a strategy for patients for whom motivation or dexterity prevents adequate brushing. Another consideration with mouthrinse is that its fluoride concentration is lower than fluoride toothpaste. The use of a non-fluoride mouthrinse after brushing with 1,000 ppm fluoride toothpaste or rinsing with 230 ppm fluoride mouthrinse after brushing with 5,000 ppm fluoride toothpaste will reduce the salivary fluoride concentration.9 Therefore, patients in this situation should be recommended to rinse prior to brushing.

Fluoride in varnish is typically 5% sodium fluoride (22,600 ppm). In a large systematic review and meta-analysis, 13 trials showed a 43% reduction in DMFS after the use of fluoride varnish on permanent teeth of adolescents.10 No trials were performed on adults; however, the implication is that fluoride varnish will prevent caries on adults as well. The mechanism by which higher concentrations of fluoride prevent caries is precipitation of calcium fluoride globules on enamel after use. These calcium fluoride globules are relatively insoluble at neutral pH and can remain on the tooth months after fluoride application. At a decreased pH, however, the calcium fluoride will dissolve and subsequently help remineralize tooth mineral with fluorapatite.11

Fluoride trays have become a standard treatment for post-radiation patients with xerostomia. A protocol of 0.4% stannous fluoride (1,000 ppm) for 5 minutes in trays daily is recommended. This treatment is based on a 1977 clinical trial that reported a 0.16 DMFS/month incidence with fluoride trays and a 2.51 DMFS/month incidence without them in radiation-induced xerostomia patients.12 Aside from increasing fluoride exposure, patients with xerostomia may also benefit from the use of buffering agents because they lack the sodium bicarbonate buffer present in saliva. Baking soda and water or any product with sodium bicarbonate may be used to increase salivary pH.13

Health Concerns With Fluoride Ingestion

With water fluoridation at levels of 0.7 ppm, the incidence of noticeable fluorosis is 12%, and fluorosis at any level is 40%.3 A dose of less than 0.05 mg/kg of total ingested fluoride is recommended, as this dose reduces the risk of fluorosis.14 The concentration of fluoride in children's toothpaste in the United States is the same amount that is present in adult toothpaste. Smaller toothpaste amounts, therefore, are recommended for younger children due to their small body size and inconsistent ability to expectorate after brushing. Thus, to ensure no more than the maximum ingested fluoride recommendation, the amount of fluoride toothpaste suggested for 6-month to 3-year-old children is a smear or rice grain-sized amount (0.10 mg), and for 3-year to 6-year-old children it is a pea-sized amount (0.25 mg) (Figure 1).15

At higher doses of ingested fluoride, concerns of toxicity arise. Common symptoms of acute fluoride toxicity include abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and headache. Higher doses of fluoride can result in issues with the central nervous system, including seizures and tetany. A dose of 5 mg/kg has been identified as likely to result in toxic effects and a dose of 15 mg/kg is considered lethal.16 The exact lethal dose is hard to define, as it is based on three case reports in which the lethal dose varied from 3.1 mg/kg to 35 mg/kg.16

Other possible negative systemic effects of fluoride include skeletal fluorosis (from fluoride binding with calcium in bones) and decreased intelligence quotient (IQ); however, findings related to these consequences are reported in areas with very high levels of fluoride in drinking water. A recent report from the National Toxicology Program (NTP) evaluated associations between IQ and fluoride levels in communities outside the United States with naturally elevated levels of fluoride in their water. The report indicated that fluoridated drinking water containing more than 1.5 ppm was associated with lower IQ in children.17 A meta-analysis of studies of fluoride levels that were consistent with community fluoride levels, rather than endemic levels, reported no association with children's IQ.18 More recently, the meta-analysis from the NTP report was published, which concluded that fluoridated drinking water was not associated with lowered IQ at levels below 1.5 ppm, unless only low risk-of-bias studies (n = 3) were considered. Low risk-of-bias studies implied confidence in the ability to measure the effects of confounding variables (ie, other environmental factors), accuracy of fluoride level measurements, and accuracy of cognitive outcome measurements.19 In order to determine the causality of the correlation between fluoride exposure and IQ, interventional studies would allow for better control of confounding variables. Another point of consideration is that the magnitude of the decreased IQ proposed by the analysis of low risk-of-bias studies was 1.14 points per 1 mg/L increase in urinary fluoride.19 For reference, a urinary fluoride concentration of 0.28 mg/L reflects a water fluoride concentration of 0.7 ppm.20

Evidence for Hydroxyapatite Toothpaste

The only compounds currently mentioned in the US Food and Drug Administration monograph regarding anticaries drugs and eligible for the anticaries claim with the American Dental Association Seal are sodium monofluorophosphate, sodium fluoride, and stannous fluoride.21 In Japan, however, the former Ministry of Health and Welfare approved "medical hydroxyapatite" for its anticaries effects, including: (1) removal of dental plaque, (2) filling surface defects on tooth, and (3) remineralizing subsurface lesions.22 The claim of filling surface defects on tooth can be substantiated from laboratory studies in which scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images showed filling of porosities in enamel.23 Remineralization of subsurface lesions is demonstrated in laboratory and in situ studies with either microhardness, polarized light microscopy, or microradiography.24,25

Although laboratory studies have demonstrated benefits of hydroxyapatite for remineralization, only a few clinical trials have evaluated hydroxyapatite toothpastes for treatment of caries. Recent systematic reviews summarized the clinical trials performed on hydroxyapatite toothpaste related to caries.25,26 Some studies examined caries prevention (rate of new caries lesions), while others examined remineralization (improvements of existing lesions). In the review, three studies compared prevention of hydroxyapatite toothpaste to a control of fluoride toothpaste. The studies measured caries progression over 6, 12, or 18 months and concluded that no statistically significant differences were seen between hydroxyapatite toothpaste and the fluoride control. Another study reported improvements of caries progression relative to a fluoride-free placebo treatment. Five other studies reported remineralization of incipient lesions using hydroxyapatite toothpaste, four of which reported it was more effective at remineralizing lesions than a fluoride control. The results of the studies presented in the reviews indicate that there is no evidence that hydroxyapatite is superior to fluoride at preventing new caries lesions. The short-term follow-up and limited number of studies with hydroxyapatite toothpaste suggest that more research is needed prior to claiming equivalent preventive effects as fluoride toothpaste. Hydroxyapatite toothpaste is not able to reduce the solubility of dental hard-tissue crystal like fluoride, which may limit its ability to prevent new carious lesions. Its greater benefit may be remineralization of incipient lesions.

The hydroxyapatite in toothpaste is categorized as either microhydroxyapatite or nanohydroxyapatite. An in vitro study reported that nanohydroxyapatite was more effective at releasing calcium and phosphate and returning surface hardness to demineralized enamel than microhydroxyapatite.27 The smaller size of nanohydroxyapatite is credited for its ability to penetrate into defects in enamel better than the larger microhydroxyapatite.22 The clinical trials that showed equivalence with fluoride toothpaste, however, used microhydroxyapatite toothpaste.25,26 The concentration of hydroxyapatite is another differentiator for hydroxyapatite toothpastes. One laboratory research trial demonstrated that a 10% solution of nanohydroxyapatite remineralized bovine teeth more than a 1% or 5% solution.27 This study has been the basis for some toothpaste manufacturers to claim that 10% nanohydroxyapatite is necessary for its efficacy.28 A common source of nanohydroxyapatite for toothpaste is from a manufacturer of nanohydroxyapatite in a 15wt% aqueous suspension. An internal study from that manufacturer suggested that the suspension at 12wt% provided optimal coverage of enamel surface porosities, which would give a final concentration of 1.8% nanohydroxyapatite.29

Due to the small size of nanohydroxyapatite crystals (<100 nm), there have been concerns regarding safety. The European Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety evaluated the nanohydroxyapatite used in the 15% aqueous solution. The committee's 2022 report stated that the rod-shaped nanohydroxyapatite only penetrated the outermost layer of buccal epithelial cells and dissolved in the stomach and therefore would not be expected to move systemically. It was not cytotoxic to epithelial or mucosal cells, had minimal cell uptake, and was not shown to induce gene mutation. The report specifically stated that these results do not apply to needle-shaped nanohydroxyapatite, which had shown systemic effects following dermal application and had cell uptake, cell injury, and genotoxic potential.30

Hydroxyapatite toothpastes are typically available as fluoride-free products for either patients who are averse to the use of fluoride or children who are at risk of fluorosis from swallowing fluoride. Some brands of toothpaste, however, contain both hydroxyapatite and fluoride. A systematic review compared four clinical trials and an in situ study that examined the ability of toothpaste with hydroxyapatite and fluoride to remineralize existing lesions.31 Of the clinical trials, only one study compared brushing with a hydroxyapatite toothpaste to brushing with a fluoride-containing toothpaste. This study found no difference in the remineralization ability between the hydroxyapatite and fluoride toothpaste and the fluoride-only toothpaste. The in situ study reported that hydroxyapatite and fluoride toothpaste remineralized extracted teeth better than the fluoride toothpaste. These results imply that there is currently minimal evidence to suggest a benefit of adding hydroxyapatite to fluoride-containing toothpaste.

Antimicrobials for Treating Dental Caries

Several antimicrobial agents have been proposed for the treatment of caries, including xylitol, povidone iodine, chlorhexidine, silver, sodium hypochlorite, and cetylpyridinium chloride.

Xylitol is a non-fermentable sugar alcohol that can be used as a sugar substitute. It also has mechanisms by which it has anticaries effects. Streptococcus mutans metabolizes xylitol into xylitol-5-phosphate, decreasing the amount of glucose that the bacteria can metabolize into lactic acid. This process also puts S mutans into an energy wasting cycle that inhibits its growth. Although xylitol-resistant S mutans may develop, this strain may have reduced adherence to tooth structure.32

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry's 2024 policy on xylitol states there is a lack of evidence of caries prevention and a concern about the dose/frequency needed.33 A Cochrane review of the use of xylitol for caries prevention concluded there was insufficient evidence to determine whether xylitol-containing products can prevent caries in children or adults.32 Despite these concerns, clinical trials have reported benefits for the use of xylitol for caries prevention. A systematic review of 10 clinical trials reported that four of the studies that used xylitol at 4.3 g/day to 10.7 g/day found a significant decrease in caries, whereas three of the studies used 2.5 g/day to 2.9 g/day and determined no significant difference in new caries. Two studies found that adding 10% xylitol to toothpaste resulted in a reduction in new caries.34 These studies imply that the effectiveness of xylitol is dependent on its dose, and a dose of 5 g/day to 6 g/day has been recommended for an anticaries effect.35 Chewing gum and mints are a common method of supplying xylitol, with several brands containing around 1 g/piece. Some chewing gums that contain xylitol, however, include as low as 0.06 to 0.17 g/piece (Figure 2).

Some health concerns are associated with xylitol. A dose of 20 g/day to 70 g/day can cause osmotic diarrhea.36 A recent study reported an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with elevated plasma xylitol.37 The study measured fasting levels of plasma xylitol, which implies that the cardiovascular risk is associated with endogenous xylitol, not dietary xylitol. The study also indicated that consuming 30 g of xylitol would increase clotting for several hours, however this dose is much higher than the recommendation for caries control. It is worth noting that xylitol can be life-threatening for dogs as doses of >0.1 g/kg can cause hypoglycemia, and doses of >0.5 g/kg can cause acute liver failure.38

The use of povidone iodine results in cell wall lysis and deactivation of proteins and nucleotides in caries-causing bacteria.39 Additionally, it inhibits the synthesis of glucans, sticky polymers that adhere bacteria to teeth.40 Clinical trials have demonstrated that application of povidone iodine to teeth can reduce the amount of S mutans present in saliva, proximal surfaces of teeth, and occlusal surfaces of teeth for up to 24 weeks.41 The use of povidone iodine prior to fluoride varnish in clinical trials of toddlers has shown significant reduction in new caries compared to fluoride varnish alone.42 Clinically, the recommended use of povidone iodine is to apply eight drops (about 0.45 mL) of 10% povidone iodine to dry teeth every 2 to 3 months (Figure 3). This application can be performed by the patient at home, and a commercially available product of vials containing 0.45 mL of 10% povidone iodine is available.43

Chlorhexidine is an antimicrobial agent that kills bacteria by disruption of their cell walls. Although chlorhexidine may reduce salivary levels of S mutans, several studies have shown no reduction in caries prevalence using a 0.12% chlorhexidine rinse,44 which is available by prescription in the United States. There is some concern with 0.12% chlorhexidine rinses as they have shown to decrease nitrate-reducing bacteria, which can lower lactic acid (improve oral pH) and produce nitric oxide (improve cardiovascular health).45 Several other antimicrobial agents can be included in mouthrinses such as silver, sodium hypochlorite, and cetylpyridinium chloride. Although these agents demonstrate antibacterial effects against S mutans, clinical evidence for their anticaries activity is currently lacking.46,47

Diagnosis of Incipient Lesions

When prevention of carious lesions is unsuccessful and incipient lesions form, minimally invasive treatment of these lesions may help to prolong the life of a tooth and avoid more invasive restorative treatments. Identifying these early lesions requires careful inspection of teeth during examinations, and several diagnostic tools may aid with detection. Caries diagnostic tools can be differentiated between those that employ radiation and those that employ light.

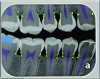

Radiation-based caries detection tools (ie, x-rays) are staples of dental practice. A new concept in radiation-based caries detection is artificial intelligence (AI) software that can overlay colorations on digital radiographs to indicate areas of radiolucency indicative of demineralization and dental caries (Figure 4). The sensitivity (true positives) of AI relative to a consensus of experts is 73% to 90% and specificity (false negatives) is 61.5% to 93%.48 Therefore, AI is only a tool to aid the dentist in identifying potential lesions. AI analysis is most useful for increasing sensitivity for identifying enamel-based caries. A study determined that AI detection of enamel caries increased the use of preventive treatments but also increased the occurrence of invasive treatment.49

Caries diagnostic tools that employ light can be differentiated into those which employ transillumination, light-induced fluorescence, or laser-induced fluorescence. Transillumination of near-infrared light works as the higher porosity in carious enamel absorbs more light and appears darker. This technology has good visualization of caries throughout the tooth but it cannot differentiate caries-based lesions and altered contrast in mineralized tissue from other sources (ie, fluorosis).50 Carious tooth structure has different fluorescence properties than sound tooth. Light-induced fluorescence works such that when carious lesions absorb light of short wavelengths, it re-emits longer wavelength light. This technology cannot visualize proximal surfaces of teeth and does not differentiate activity of carious lesions.50 Laser-induced fluorescence derives fluorescence from activating protoporphyrin, a photosensitive pigment that is a metabolic product of caries-causing bacteria. Therefore, this technology is claimed to identify caries activity. This technology does not provide a visual map of caries like other aids, but rather generates a number that indicates caries severity.50

Small molecules can also be used to help visually identify incipient lesions. One commercial product employs negatively charged starch nanoparticles (100 nm) that selectively bond to carious enamel. They are tagged with a fluorescent marker that fluoresces when illuminated by a dental curing light (Figure 5).51 Another product contains a hemoglobin-based dye that bonds to exposed hydroxyapatite in subsurface enamel porosity. The stain is visible with ambient lighting.52

Minimally Invasive Treatment for Incipient Lesions

Contemporary strategies for remineralization or repair of incipient lesions include self-assembling peptides, casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate pastes, and resin infiltration. Silver diamine fluoride (SDF) is another minimally invasive treatment for arresting caries that is typically used for cavitated lesions. There is some evidence, however, that SDF may be used to slow progression of incipient, noncavitated interproximal and occlusal lesions.53,54

Enamel matrix is present during odontogenesis to aid with hydroxyapatite crystal formation, however it is not present in the mature tooth. A novel concept for remineralization of incipient lesions is to create an artificially derived self-assembling peptide to serve as a scaffold to mimic the function of enamel matrix (Figure 6). P11-4 is a peptide that can self-assemble into ribbons with binding sites for calcium ions. The spacing between the calcium binding sites is designed to replicate the interatomic distance between columnar calcium in hydroxyapatite crystal. These peptides have been shown to access subsurface demineralization and induce remineralization.55 Clinical trials of a commercial product containing P11-4 self-assembling peptides have shown evidence for arrest of lesions as well as decreasing lesion size.56 The treatment has shown positive results for both smooth-surface and interproximal lesions.56,57

Another treatment strategy is supplying bioavailable calcium and phosphate to aid in the remineralization of enamel defects and subsurface lesions. The challenge with calcium phosphate remineralization treatments is their low solubility in saliva. If the calcium and phosphate are precipitated into a solid phase, they are not bioavailable for remineralization. Calcium phosphate can be added in a crystalline form (such as tricalcium phosphate or bioactive glass) or an amorphous form (such as amorphous calcium phosphate [ACP]). With a less structured order, the amorphous form is more soluble than the crystalline form. To improve the solubility and bioavailability of ACP, it may be bound with a stabilizing protein, such as milk-based casein.58 Phosphopeptides in casein have regions that are able to weakly bind with calcium and phosphate and prevent their crystalline growth and precipitation. Additionally, these binding regions can also bind to calcium in damaged enamel, and therefore these peptides can "deliver" calcium and phosphate from saliva to the tooth.59 Commercial products are available that contain casein phosphopeptide-stabilized amorphous calcium phosphate complexes (CPP-ACP) as well as casein phosphopeptide-stabilized amorphous calcium fluoride phosphate complexes (CPP-ACFP) in pastes, gums, and varnishes. Evidence for the clinical benefit of CPP-ACP paste over fluoride toothpaste for prevention of new lesions is questionable, however there is some evidence for a benefit of CPP-ACP for remineralization of incipient lesions.60 CPP-ACFP has not shown clinical benefit over CPP-ACP or fluoride toothpaste for remineralization.61

Resin infiltration is a method to treat incipient caries lesions by infiltrating unfilled resin through surface porosities into facial and interproximal subsurface lesions (Figure 7). Although this technique is not a form of remineralization, clinical trials have concluded that resin infiltration can arrest noncavitated caries lesions.62

Conclusion

Fluoride remains the staple of prevention, as its incorporation into apatite crystal allows resistance to future acid dissolution. Patients concerned about fluorosis or potential health issues associated with fluoride may consider hydroxyapatite toothpaste, although evidence for its ability to prevent new carious lesions is minimal. Innovations in caries diagnostics, including AI, light-based tools, and small molecules, can help in early detection of incipient lesions. Remineralization strategies such as hydroxyapatite, self-assembling peptides, or CPP-ACP offer promising options for incipient lesions. Antibacterial products may aid in managing patients with caries risk factors. Finally, a caries risk plan must prioritize a patient's willingness to participate in reducing caries risk factors by modifying diet and hygiene practices.

About the Author

Nathaniel C. Lawson, DMD, PhD

Director, Division of Biomaterials, and Program Director of the Biomaterials Residency Program, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Dentistry, Birmingham, Alabama; General Dentist, UAB Faculty Practice

Queries to the author regarding this course may be submitted to authorqueries@conexiant.com.

References

1. Simmer JP, Hardy NC, Chinoy AF, et al. How fluoride protects dental enamel from demineralization. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2020;10(2):134-141.

2. Arnold FA Jr. Grand Rapids fluoridation study; results pertaining to the eleventh year of fluoridation. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1957;47(5):539-545.

3. Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Walsh T, Lewis SR, et al. Water fluoridation for the prevention of dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;10(10):CD010856.

4. Pessan JP, Conceição JM, Grizzo LT, et al. Intraoral fluoride levels after use of conventional and high-fluoride dentifrices. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19(4):955-958.

5. Issa AI, Toumba KJ. Oral fluoride retention in saliva following toothbrushing with child and adult dentifrices with and without water rinsing. Caries Res. 2004;38(1):15-19.

6. Marinho VC, Chong LY, Worthington HV, Walsh T. Fluoride mouthrinses for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;7(7):CD002284.

7. Axelsson P, Paulander J, Nordkvist K, Karlsson R. Effect of fluoride containing dentifrice, mouthrinsing, and varnish on approximal dental caries in a 3-year clinical trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15(4):177-180.

8. Blinkhorn AS, Holloway PJ, Davies TG. Combined effects of a fluoride dentifrice and mouthrinse on the incidence of dental caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1983;11(1):7-11.

9. Mystikos C, Yoshino T, Ramberg P, Birkhed D. Effect of post-brushing mouthrinse solutions on salivary fluoride retention. Swed Dent J. 2011;35(1):17-24.

10. Marinho VC, Worthington HV, Walsh T, Clarkson JE. Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2013;2013(7):CD002279.

11. Rošin-Grget K, Peroš K, Sutej I, Bašić K. The cariostatic mechanisms of fluoride. Acta Med Acad. 2013;42(2):179-188.

12. Dreizen S, Brown LR, Daly TE, Drane JB. Prevention of xerostomia-related dental caries in irradiated cancer patients. J Dent Res.1977;56(2):99-104.

13. Chandel S, Khan MA, Singh N, et al. The effect of sodium bicarbonate oral rinse on salivary pH and oral microflora: a prospective cohort study. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2017;8(2):106-109.

14. Warren JJ, Levy SM, Broffitt B, et al. Considerations on optimal fluoride intake using dental fluorosis and dental caries outcomes-a longitudinal study. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69(2):111-115.

15. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride therapy. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, IL: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2024:351-357.

16. Whitford GM. Acute and chronic fluoride toxicity. J Dent Res.1992;71(5):1249-1254.

17. National Toxicology Program (NTP). NTP monograph on the state of the science concerning fluoride exposure and neurodevelopment and cognition: a systematic review. Research Triangle Park, NC: National Toxicology Program; NTP Monograph 08. August 2024. https://doi.org/10.22427/NTP-MGRAPH-8. Accessed January 23, 2025.

18. Kumar JV, Moss ME, Liu H, Fisher-Owens S. Association between low fluoride exposure and children's intelligence: a meta-analysis relevant to community water fluoridation. Public Health.2023;219:73-84.

19. Taylor KW, Eftim SE, Sibrizzi CA, et al. Fluoride exposure and children's IQ scores: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2025; doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.5542.

20. Veneri F, Vinceti M, Generali L, et al. Fluoride exposure and cognitive neurodevelopment: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2023;221:115239.

21. US Food and Drug Administration. Part 355. Anticaries Drug Products for Over-the-Counter Human Use. Updated August 30, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm?fr=355.50. Accessed January 23, 2025.

22. Pushpalatha C, Gayathri VS, Sowmya SV, et al. Nanohydroxyapatite in dentistry: a comprehensive review. Saudi Dent J. 2023;35(6):741-752.

23. Vitiello F, Tosco V, Monterubbianesi R, et al. Remineralization efficacy of four remineralizing agents on artificial enamel lesions: SEM-EDS investigation. Materials (Basel). 2022;15(13):4398.

24. Imran E, Cooper PR, Ratnayake J, et al. Potential beneficial effects of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles on caries lesions in vitro - a review of the literature. Dent J (Basel). 2023;11(2):40.

25. Limeback H, Enax J, Meyer F. Improving oral health with fluoride-free calcium-phosphate-based biomimetic toothpastes: an update of the clinical evidence. Biomimetics (Basel). 2023;8(4):331.

26. Limeback H, Enax J, Meyer F. Biomimetic hydroxyapatite and caries prevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Dent Hyg. 2021;55(3):148-159.

27. Huang SB, Gao SS, Yu HY. Effect of nano-hydroxyapatite concentration on remineralization of initial enamel lesion in vitro. Biomed Mater.2009;4(3):034104.

28. Pepla E, Besharat LK, Palaia G, et al. Nano-hydroxyapatite and its applications in preventive, restorative and regenerative dentistry: a review of literature. Ann Stomatol (Roma). 2014;5(3):108-114.

29. nanoXim CarePaste. White Paper, Enamel Remineralization. Fluidinova, S.A. https://www.fluidinova.com/products/carepaste. Accessed January 23, 2025.

30. SCCS (Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety), Opinion on Hydroxyapatite (nano), preliminary version of 27-28 October 2020, final version of 30-31 March 2021, SCCS/1624/2020.

31. Guanipa Ortiz MI, Gomes de Oliveira S, de Melo Alencar C, et al. Remineralizing effect of the association of nano-hydroxyapatite and fluoride in the treatment of initial lesions of the enamel: a systematic review. J Dent. 2024;145:104973.

32. Riley P, Moore D, Ahmed F, et al. Xylitol-containing products for preventing dental caries in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2015;2015(3):CD010743.

33. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on use of xylitol in pediatric dentistry. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, IL: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2024:114-116.

34. Marghalani AA, Guinto E, Phan M, et al. Effectiveness of xylitol in reducing dental caries in children. Pediatr Dent. 2017;39(2):103-110.

35. Nayak PA, Nayak UA, Khandelwal V. The effect of xylitol on dental caries and oral flora. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent.2014;6:89-94.

36. Mäkinen KK. Gastrointestinal disturbances associated with the consumption of sugar alcohols with special consideration of xylitol: scientific review and instructions for dentists and other health-care professionals. Int J Dent. 2016;2016:5967907.

37. Witkowski M, Nemet I, Li XS, et al. Xylitol is prothrombotic and associated with cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(27):2439-2452.

38. Piscitelli CM, Dunayer EK, Aumann M. Xylitol toxicity in dogs. Compend Contin Educ Vet.2010;32(2):E1-E4.

39. Brookes Z, McGrath C, McCullough M. Antimicrobial mouthwashes: an overview of mechanisms - what do we still need to know? Int Dent J. 2023;73 suppl 2:S64-S68.

40. Furiga A, Dols-Lafargue M, Heyraud A, et al. Effect of antiplaque compounds and mouthrinses on the activity of glucosyltransferases from Streptococcus sobrinus and insoluble glucan production. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2008;23(5):391-400.

41. Caufield PW, Gibbons RJ. Suppression of Streptococcus mutans in the mouths of humans by a dental prophylaxis and topically-applied iodine. J Dent Res. 1979;58(4):1317-1326.

42. Horst JA, Tanzer JM, Milgrom PM. Fluorides and other preventive strategies for tooth decay. Dent Clin North Am. 2018;62(2):207-234.

43. CareQuest Institute for Oral Health. The Non-Invasive Caries Therapy Guide. Boston, MA: April 2023. https://www.carequest.org/content/non-invasive-caries-therapy-guide. Accessed January 23, 2025.

44. Autio-Gold J. The role of chlorhexidine in caries prevention. Oper Dent. 2008;33(6):710-716.

45. Brookes ZLS, Belfield LA, Ashworth A, et al. Effects of chlorhexidine mouthwash on the oral microbiome. J Dent. 2021;113:103768.

46. Evans A, Leishman SJ, Walsh LJ, Seow WK. Inhibitory effects of antiseptic mouthrinses on Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sanguinis and Lactobacillus acidophilus. Aust Dent J. 2015;60(2):247-254.

47. Yin IX, Zhao IS, Mei ML, et al. Synthesis and characterization of fluoridated silver nanoparticles and their potential as a non-staining anti-caries agent. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020;15:3207-3215.

48. Revilla-León M, Gómez-Polo M, Vyas S, et al. Artificial intelligence applications in restorative dentistry: a systematic review. J Prosthet Dent. 2022;128(5):867-875.

49. Mertens S, Krois J, Cantu AG, et al. Artificial intelligence for caries detection: randomized trial. J Dent. 2021;115:103849.

50. Chan EK, Wah YY, Lam WY, et al. Use of digital diagnostic aids for initial caries detection: a review. Dent J (Basel). 2023;11(10):232.

51. Jones NA, Chang SR, Troske WJ, et al. Nanoparticle-based targeting and detection of microcavities. Adv Healthc Mater.2017;6(1). doi: 10.1002/adhm.201600883.

52. Lippert F, Eder JS, Eckert GJ, et al. Detection of artificial enamel caries-like lesions with a blue hydroxyapatite-binding porosity probe. J Dent. 2023;135:104601.

53. Polacek J, Malhi N, Yang YJ, et al. Silver diamine fluoride and progression of incipient approximal caries in permanent teeth: a retrospective study. Pediatr Dent.2021;43(6):475-480.

54. Braga MM, Mendes FM, De Benedetto MS, Imparato JC. Effect of silver diammine fluoride on incipient caries lesions in erupting permanent first molars: a pilot study. J Dent Child (Chic). 2009;76(1):28-33.

55. Kind L, Stevanovic S, Wuttig S, et al. Biomimetic remineralization of carious lesions by self-assembling peptide. J Dent Res.2017;96(7):790-797.

56. Keeper JH, Kibbe LJ, Thakkar-Samtani M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of self-assembling peptide P11-4 on arrest, cavitation, and progression of initial caries lesions. J Am Dent Assoc.2023;154(7):580-591.e11.

57. Godenzi D, Bommer C, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, et al. Remineralizing potential of the biomimetic P11-4 self-assembling peptide on noncavitated caries lesions: a retrospective cohort study evaluating semistandardized before-and-after radiographs. J Am Dent Assoc.2023;154(10):885-896.e9.

58. Cochrane NJ, Cai F, Huq NL, et al. New approaches to enhanced remineralization of tooth enamel. J Dent Res. 2010;89(11):1187-1197.

59. Reynolds EC. Anticariogenic complexes of amorphous calcium phosphate stabilized by casein phosphopeptides: a review. Spec Care Dentist. 1998;18(1):8-16.

60. Raphael S, Blinkhorn A. Is there a place for Tooth Mousse in the prevention and treatment of early dental caries? A systematic review. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15(1):113.

61. Golzio Navarro Cavalcante B, Schulze Wenning A, Szabó B, et al. Combined casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate and fluoride is not superior to fluoride alone in early carious lesions: a meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2024;58(1):1-16.

62. Chatzimarkou S, Koletsi D, Kavvadia K. The effect of resin infiltration on proximal caries lesions in primary and permanent teeth. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Dent.2018;77:8-17.