You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

Root amputation, or root resection, is the removal of a compromised root of a multirooted tooth to prolong the tooth's functionality in a disease-free state. The procedure permits the tooth to be retained with its existing restoration while allowing the surrounding bone to be maintained in a manner that enables the resolution of persisting endodontic and/or periodontal pathology. Factors associated with appropriate case selection, proper surgical technique, and post-treatment management converge to make root resection a viable treatment modality that takes advantage of the accuracy afforded by today's microsurgical treatment processes.

Compromised Conditions

Apical periodontitis, periradicular periodontitis, and marginal periodontitis are disease processes that frequently result in the loss of teeth over time due to supporting bone and soft-tissue attachment loss. Roots of teeth can become compromised through many avenues, all of which share a similar outcome: an inflammatory-based reaction leading to the loss of supporting bone.

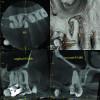

Such compromised conditions include vertically fractured roots, perforated roots, periodontally compromised roots due to furcation or root proximity issues, communicating endodontic-periodontal defects compounded by short root lengths, unresponsive furcation defects, significant untreatable external resorptive defects, and so on (Figure 1 through Figure 4). When conditions such as these affect single-rooted teeth, extraction is often the only way to eliminate the resultant pathology. With multirooted teeth, however, an additional option exists: definitively removing the cause of the pathology while simultaneously retaining the tooth in a functional state, which has published favorable survivability rates of upwards of 80% to 90%.1-3 If performed appropriately by taking into account the factors described in this article, this functional state can be maintainable for the long term, with a median survival time of 6 to 20 years.3-6

The resection of a root from a multirooted tooth is a surgical procedure in which the affected root is surgically removed from the tooth, and the remaining cantilevered portion of the tooth is then contoured for comfort, esthetics, and most importantly, access for cleansability. The resection of an untreatable tooth root in order to save the tooth has been an available and well-understood treatment option for many years.7 However, the benefits afforded by more recently developed microscopic treatment methods coupled with information that has been gleaned from years of follow-ups have created a predictable pathway for clinicians to maximize the outcomes of this treatment option, with patients often being able to keep their tooth and avoid complete extraction altogether. The use of a surgical operating microscope enables accurate resection of the affected root and permits the precise shaping of the underside of the remaining tooth structure so that hidden lips and ledges may be appropriately managed. This is especially crucial with more complicated maxillary molar root resection cases where the underside tooth structure often has to blend into two roots, versus only one in mandibular molars.8 Hemostasis techniques involving the use of lidocaine with higher epinephrine concentration (1:50,000 versus 1:100,000 epinephrine concentration) as well as epinephrine-impregnated cotton pellets are reliable isolation techniques adapted from endodontic microsurgery and are crucial when isolating the underside of the tooth to allow placement of a bonded restorative material to seal the root canal chamber.

Case Selection

The objective of removing an affected root is to eliminate the avenue for bacterial ingress or accumulation that is the reason for the resultant chronic or acute inflammatory reaction. Case selection is an important factor when considering root resection, starting with the anatomic root configuration of the tooth as a whole. This treatment option is applicable for most multirooted teeth; however, it is not indicated for teeth that have completely fused roots, where the individual resection of the affected root cannot be done in a manner that would eliminate the bacterial pathway into the tissues. Outcome studies have also shown that the effects of occlusal forces in the mouth negatively affect the outcome of teeth when a distal or distobuccal root is removed from a tooth, because this results in an overhanging cantilever in the distal direction that is more significantly impacted by occlusal forces.2,9 Despite this finding, many cases can still be successfully treated with root resection and should be considered for it.

A patient's overall plaque control is an important consideration in case selection, as this factor helps determine not only whether the root resection option should be considered in the first place, but also whether the patient can maintain the tooth in the event splinting is necessary. If a root is resected and increased mobility results from the loss of the root, splinting may then be considered, although splinting will block the patient's ability to floss interproximally and under the cantilevered portion of the tooth. Similar to a fixed bridge abutment, excellent plaque control is essential on a root-resected tooth that is splinted to its neighbor to achieve long-term success. Patients who undergo root resection procedures may be overly cautious and/or hesitant to brush thoroughly around their treated teeth even after a number of years post-treatment, which can invariably lead to increased plaque accumulation. As the authors have observed through years of following clinical cases over time, poor plaque control can lead to recurrent decay on the treated and adjacent teeth and subsequent increased bone loss below the cantilevered portion of the tooth, which can start to undermine the remaining retained roots (Figure 5).

Treatment Factors

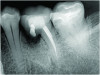

A number of treatment factors must be considered and certain objectives accomplished in order to create a cleansable tooth. Starting with the resection of the root, there can be no residual root stub remaining so that a furcation does not persist. The most cleansable shape after resecting a root is achieved by removing the root such that a smooth, flowing angle of departure exists from the retained root to just below the contact space with the adjacent tooth, as can be seen in Figure 6. In many cases this may result in an esthetic compromise; however, if the cantilevered portion of the tooth is flat or creates an uncleansable trap for bacteria to accumulate, the case will have an elevated risk of developing recurrent decay and increased crestal bone loss over time. The importance of preventing a plaque trap via a cleansable shape typically outweighs the esthetic compromise. While achieving this objective can be technically difficult, especially on the lingual side of mandibular molars and on the mesiopalatal aspect of maxillary molar mesiobuccal root resections, it is a crucial step in the surgical process.

Figure 6, which shows a clinical image of a tooth No. 14 with a mesiobuccal root resection, highlights the desired cantilever contour result. Note that no root stub exists and the cantilever flows smoothly to the retained palatal and distobuccal roots and progresses mesially to a point below the contact space with the adjacent tooth.

During the resection process, directly visualizing the smooth transition to the retained distobuccal and palatal roots is essential and made possible by utilizing an operating microscope. Note that in Figure 6 the underside of the tooth has been restored with a resin-modified glass-ionomer (RMGI) restorative material. The restoration of the underside of the remaining tooth is important to satisfy the objective of a maximally cleansable result. A new restoration to seal the underside of the cantilevered section of the tooth will almost always be needed, except in the few cases where the resection of the root and shaping of the cantilevered section results in the exposure of a perfectly smooth existing restoration with no voids. Most core buildups do not extend into the root canal orifices far enough to satisfy this condition, however, which is why placing a new restoration on the underside of the cantilevered portion should be planned in almost every case. An additional benefit of placing a new restoration that covers much of the cantilevered underside of the tooth is that the underside of the tooth will become more resistant to decay since the restorative material itself cannot directly decay.

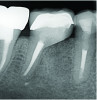

Figure 7 shows an example of a mesial root resection that satisfies the objective of creating a smooth contour from the distal root toward the contact space on the mesial aspect, with no overhang, especially toward the lingual side of the root. This image also demonstrates an appropriate restoration placed to seal the underside of the cantilevered portion of the root.

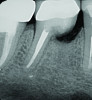

As clinically observed by the authors, most root resection cases in which a graft is placed (see "Graft Placement" below) will heal over time with the crestal bone stabilizing at a point that is 1 mm to 3 mm below the cantilevered portion of the tooth. This fact reinforces the importance of having a more coronal resection level and not leaving a stub of the resected root; a stub will extend further apically and over time result in greater crestal bone loss and future problems related to plaque control and periodontal issues. The case shown in Figure 8 is a 5-year post-treatment image of tooth No. 30, depicting the anticipated healing outcome of a grafted resected root socket. It demonstrates the result of well-managed plaque control and optimally maintained crestal bone.

Graft Placement

When a root is resected and removed, an empty socket is left behind. If left to heal without assistance, the socket can result in greater exposure of the remaining roots, decreasing the tooth's survivability.6 Placement of an allograft to encourage maximal hard-tissue healing in the socket is an essential part of the root resection treatment process, yielding several important benefits. First, a graft provides greater bone support of the remaining roots versus the use of no graft.10 Second, physical blockage of soft-tissue collapse into the socket permits better postoperative esthetics and increased crestal bone height in the socket.10 Third, a graft allows for accelerated and maximal bone healing of the socket of the removed root, which facilitates future implant placement in the event complete tooth failure were to occur in the future. In many cases of mandibular molar mesial root resections, the anatomic location of the mesial root is often closest to the region where a future implant would be placed, if needed.

While grafting can be placed into a socket such that the level of the graft is in contact with the cantilevered portion of the tooth, the authors have observed that over time the crestal bone level will typically stabilize 1 mm to 3 mm below the cantilevered section (Figure 9 and Figure 10). The resultant level of the grafted crestal bone over time is dependent primarily on the patient's plaque control abilities, which are directly related to the contour achieved through the resection process, thus emphasizing the importance of proper resection and contouring during the procedure.

Facilitating Ease of Maintenance

Like many technique-sensitive treatment procedures in dentistry, root resection can be a highly successful treatment option when performed properly, taking into account all of the potential outcome-influencing factors. The goal is to remove the source of the disease, which is a nonrepairable root that when removed through root resection will definitively eliminate the pathology.

The challenge with root resection then lies with creating a resulting situation that has a cleansable shape that can be hygienically maintained at a high level. In cases of parafunctional loading or where increased mobility has resulted after the removal of the root, splinting likely will need to be utilized. Splinting increases the challenge of maintaining the area and keeping it free of plaque. In cases where splinting was performed, creating an aggressive resection is especially important to enable adequate cleaning over time (Figure 11).

Cost-Effectiveness of Root Resection

With the prevalence of the use of implant-supported crowns to address compromised teeth, it is often overlooked that a multirooted tooth can still be saved even when it has a vertically fractured root, a severe periodontal problem, root decay, or nonrepairable resorption. Especially in light of the incidence of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis,11 combined with the higher costs of implant dentistry and the increased number of surgical interventions-which can introduce significant potential complications associated with extracting a tooth and replacing it with an implant-supported crown-the efficiency and effectiveness of the single-visit treatment involved with performing a root resection should not be overlooked.

Conclusion

Root resection is a valuable treatment option for retaining compromised multirooted teeth. By removing the affected root and addressing the underlying pathology, this procedure allows for the preservation of tooth functionality while maintaining surrounding bone health. Advances in microsurgical techniques and careful case selection have enhanced the predictability of successful outcomes, with long-term survival rates that rival alternative treatments. Root resection not only provides a cost-effective solution but also mitigates the risks associated with dental implants, such as peri-implantitis. With proper execution and meticulous patient hygiene, root resection offers a reliable path to preserving natural dentition.

About the Authors

Garrett Guess, DDS

Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Endodontics, University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Private Practice in Endodontics, La Jolla, California

Sam Kratchman, DMD

Associate Professor, Department of Endodontics, University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Bekir Karabucak, DMD, MS

Chair and Professor of Endodontics, Director of Postdoctoral Endodontics Program, Department of Endodontics, University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Queries to the author regarding this course may be submitted to authorqueries@conexiant.com.

References

1. Setzer FC, Shou H, Kulwattanaporn P, et al. Outcome of crown and root resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. J Endod. 2019;45(1):6-19.

2. Fugazzotto PA. A comparison of the success of root resected molars and molar position implants in function in a private practice: results of up to 15-plus years. J Periodontol.2001;72(8):1113-1123.

3. Derks H, Westheide D, Pfefferle T, et al. Retention of molars after root-resective therapy: a retrospective evaluation of up to 30 years. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22(3):1327-1335.

4. El Sayed N, Cosgarea R, Rahim S, et al. Patient-, tooth-, and dentist-related factors influencing long-term tooth retention after resective therapy in an academic setting - a retrospective study. Clin Oral Investig.2020;24(7):2341-2349.

5. Lee KL, Corbet EF, Leung WK. Survival of molar teeth after resective periodontal therapy - a retrospective study. J Clin Periodontol.2012;39(9):850-860.

6. Alassadi M, Qazi M, Ravida A, et al. Outcomes of root resection therapy up to 16.8 years: a retrospective study in an academic setting. J Periodontol.2020;91(4):493-500.

7. Schmitt SM, Brown FH. Management of root-amputated maxillary molar teeth: periodontal and prosthetic considerations. J Prosthet Dent. 1989;61(6):648-652.

8. Park SY, Shin SY, Yang SM, Kye SB. Factors influencing the outcome of root-resection therapy in molars: a 10-year retrospective study. J Periodontol.2009;80(1):32-40.

9. Langer B, Stein SD, Wagenberg B. An evaluation of root resections: a ten-year study. J Periodontol. 1981;52(12):719-722.

10. Avila-Ortiz G, Chambrone L, Vignoletti F. Effect of alveolar ridge preservation interventions following tooth extraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2019;46(suppl 21):195-223.

11. Derks J, Tomasi C. Peri-implant health and disease. A systematic review of current epidemiology. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(suppl 16):S158-S171.