You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

The use of dental implants has quickly become a primary method for replacing missing teeth due to their high level of predictability and patient acceptance.1-4 By 2006, dentists in the United States had placed 5.5 million dental implants, and this number continues to grow.5 As of 2007, more than 30 million Americans were reported to have missing teeth in one or both jaws.6 With the aging population increasingly seeking dental implants to replace missing teeth, a growing number of general dentists and dental specialists are being trained to place and restore them.

Despite the ever-increasing demand for implant-supported restorations, the pain patients experience and the effectiveness of analgesic interventions following the surgical component of treatment has not been well studied. Hundreds of papers have been published on the pain and effectiveness of analgesic interventions following the removal of impacted third molars. In contrast, a PubMed search between the years 1970 and 2012 using the MeSH terms dental implant pain or postsurgical dental implant pain revealed six papers in the literature evaluating the intensity or duration of implant surgery pain or the effectiveness of analgesic therapy.7-12 The overwhelming majority of participants enrolled in impacted third molar pain studies are young healthy adults, whereas implant patients tend to be significantly older, with a variety of concomitant medical conditions requiring the intake of multiple medications to treat these comorbid conditions.

Ketorolac is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) with FDA approval for the short-term (5 days or less) treatment of moderate to moderately severe pain. It is available as an oral, parenteral, and most recently (May 17, 2010) an intranasal formulation. This newest formulation (SPRIX®, Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc., www.luitpold.com) comes in a disposable, multi-dose, metered spray device that allows patients to self-administer the drug outside of the hospital setting.13-16 The recommended dose is 31.5 mg (one 15.75 mg spray in each nostril) every 6 to 8 hours for patients under the age of 65 years, with half this dose (one 15.75 mg spray in only one nostril) recommended for those 65 years or older.16 Intranasal ketorolac has demonstrated efficacy in patients experiencing abdominal, orthopedic, and impacted third molar surgery pain.13,17-19 Its absorption from the nasal mucosa is as rapid as the intramuscular administration of the drug.20

The purpose of this open-labeled multi-dose pilot study was to characterize the nature of postsurgical pain in patients undergoing routine dental implant surgery with respect to the percentage of participants requiring postoperative pain medication and their duration of analgesic dosing. The authors also explored the efficacy and tolerability of intranasal ketorolac in these patients.

Methods

The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the protocol and informed consent form, and the trial was listed in ClinicalTrials.gov under the identifier NCT01490931. Patients between the ages of 18 to 64 years of age who were scheduled for the placement of one to three dental implants without the need for significant bone grafting were invited to participate in this open-label study. Key exclusion criteria included NSAID intolerance or allergy, the use of bupivacaine as a local anesthetic, the need for sedative drugs other than nitrous oxide, pregnancy, and the use of any antiplatelet or anticoagulant agent other than low-dose (81 mg to 325 mg) aspirin.

Dental implant surgery was carried out according to standard of care. Patients self-administered the ketorolac nasal spray (15.75 mg in each nostril) according to the package insert guidelines and under the supervision of the research coordinator or one of the investigators (RB) once they began to experience at least moderate pain indicated by scores of ≥ 40 mm on a 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS, 0 = no pain, 100 = worst possible pain) and a score of ≥ 2 on a 0 to 3 ordinal scale (none, mild, moderate, or severe pain). Pain intensity on the VAS and the ordinal scale and pain relief on a 0 to 4 ordinal scale (no relief, a little relief, some relief, a lot of relief, complete relief) were assessed for 6 hours, as was the onset of first perceptible and meaningful relief employing a double stopwatch technique.21 Acetaminophen 650 mg was available as a rescue analgesic if sufficient pain relief was not obtained or pain relief dissipated before 6 hours. At the 6-hour time point or at the time of requesting rescue analgesic, patients gave their overall impression of the intranasal ketorolac from poor to excellent.21

Patients then transitioned into a multi-dose take-home phase of the study where they were allowed to administer the ketorolac nasal spray every 6 hours on a prn basis when and if they felt the need to medicate for pain control. They completed a take-home diary where the time of dosing, the pain intensity at dosing, the time of any rescue acetaminophen they ingested, and any adverse events they may have experienced were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Time-effect curves for changes in pain intensity and pain relief, as well as the cumulative percentage of participants re-medicating with acetaminophen at each time point through the initial 6-hour post-dosing period were constructed. The percentage of patients who rated intranasal ketorolac as poor, fair, good, very good, or excellent was also calculated. Changes in pain intensity on both the VAS and the 0 to 3 ordinal scale were statistically compared to baseline pain utilizing paired t-tests with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons. The median onsets of first perceptible and meaningful relief (with 95% confidence intervals) were calculated and then used to construct Kaplan-Meier curves of the distribution of pain relief times.

Results

A total of 31 patients consented to the study and 25 were dosed with intranasal ketorolac 31.5 mg. Of the six patients who were not dosed one reported a history of aspirin-sensitive asthma immediately before surgery (an absolute contraindication for the administration of all NSAIDs), another had a body mass index (BMI) of 31 which at the time precluded enrollment (maximum BMI was 29 until an IRB-approved amendment increased it to 33), and a third did not receive his implants because of the need for significant bone grafting during surgery. Three patients who received their implants did not achieve the required VAS pain intensity score of 40 mm within 4 hours of the completion of their surgery. Therefore, 89% (25/28) of the participants obtained a level of at least moderate postsurgical pain within 4 hours after the placement of one to three implants. The demographic characteristics and the mean baseline pain score of the study population are shown in Table 1.

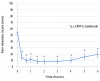

As displayed in Figure 1, mean VAS pain intensity scores rapidly decreased following self-administration of intranasal ketorolac 31.5 mg. By the 20-minute time point, the mean VAS score had decreased from 54.4 mm to 14.8 mm. Mean peak reduction in pain intensity appeared to occur within 40 minutes, with the analgesic effect still being prominent at 6 hours (a mean VAS of 19.5 mm). All mean VAS pain intensity scores from 20 minutes through 6 hours were significantly lower (p < 0.0001) than the mean baseline pain intensity score prior to dosing. The reduction in pain intensity on the 0 to 3 ordinal scale mirrored the VAS data with respect to time course and magnitude of effect.

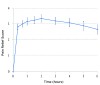

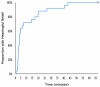

The time effect curve for mean pain relief (Figure 2) also displayed a rapid onset (within 20 minutes), high peak effects between 40 minutes and 4 hours, and an apparent duration of action at least through 6 hours. The median onsets of first perceptible and meaningful pain relief were 86 seconds (95% confidence interval; 64 to 172 sec) and 172 seconds (95% confidence interval; 132 to 735 sec), respectively, again confirming the rapid onset of the drug. The Kaplan-Meier curve of the times to meaningful relief among participants is shown in Figure 3. Only one participant did not obtain meaningful pain relief.

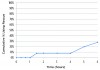

Figure 4 illustrates the cumulative percentage of participants requiring rescue analgesic (aceta-minophen 650 mg) within 6 hours. Only 8% (2/25) of patients ingested rescue analgesic by 4 hours post-dosing, with 28% (7/25) patients doing so by 6 hours. Overall impressions (Figure 5) of intranasal ketorolac were extremely favorable, with 92% of patients rating the drug as very good or excellent.

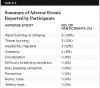

Twenty of the 25 patients (80%) who completed the initial 6-hour evaluation period required additional doses of intranasal ketorolac and/or rescue medication at home. Table 2 shows the percentage of patients still administering pain medication and the mean number of doses they were taking per day during the 5-day evaluation period. On days two through four, one or two patients ingested supplemental acetaminophen in addition to intranasal ketorolac, while one patient discontinued intranasal ketorolac for inadequate pain control and required a prescription containing an opioid analgesic through day five. The most common side effect reported by patients during the initial dosing and take-home dosing periods was transient nasal burning (36% or 9/25) on drug administration. Table 3 lists the side effects reported by study patients. No patient discontinued taking intranasal ketorolac because of an adverse event.

Discussion

It has previously been reported that the pain patients experience after routine dental implant surgery is generally mild in nature.7,10-12 In the current study, 25 of 28 subjects receiving one to three implants without significant bone grafting experienced pain of at least a moderate intensity within 4 hours after the completion of surgery. It has been reported that the experience of the operator (periodontist or oral surgeon versus periodontal resident) appears to correlate with the degree of dental implant postoperative pain following implant surgery.12 In the current study, the three subjects who did not require analgesic medication within the 4 hours immediately following their surgery had their implants placed by residents. Of the 25 participants who dosed with intranasal ketorolac, residents performed 18 of the surgeries, and an experienced periodontist or oral surgeon performed seven. However, the authors cannot rule out that average pain scores could have been less if only experienced clinicians performed the surgeries. More than 50% of this study’s cohort required analgesic medication for at least 3 days following what is considered routine dental implant surgery. It is likely that subjects with more traumatic surgery would experience greater levels of pain and dose more frequently for a longer period of time.10

In the participants in this study, intranasal ketorolac displayed a rapid analgesic onset, high peak effects, and an acceptable duration of action. A rapid onset of analgesic activity is desirable because it enhances patient comfort and reduces the chance of excessive drug dosing. If additional analgesics are needed for breakthrough pain within the 6-hour dosing interval, acetaminophen or an acetaminophen/opioid combination drug can be safely given in conjunction with NSAIDs like ketorolac.17-19,22,23 According to the package insert, other NSAIDs including preparations containing ibuprofen or aspirin should not be administered concurrently with any formulation of ketorolac because of the risk of additive gastrointestinal bleeding and/or toxicity.16 The most common adverse event experienced by participants in this study was a burning or stinging feeling of the nasal mucosa immediately after dosing, which dissipated rapidly. This common side effect was reported by participants in other studies and is listed in the package insert of the drug.16,17,19,24

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as intranasal ketorolac, should represent the first line drugs for most types of postsurgical dental pain because of their proven efficacy and favorable side-effect profile.25 Unlike the oral formulation of ketorolac, which according to package insert guidelines should only be prescribed for patients who were originally taking parenteral ketorolac for pain,26 the intranasal formulation can be used as the initial pain treatment. Because of ketorolac’s high ulcerogenic potential, intranasal ketorolac should still not be used for more than 5 days.16 Additional black box warnings on the package insert of intranasal ketorolac include contraindications in patients with poor kidney function and those with a high bleeding risk.16 While opioid-containing analgesics remain the most popular drugs in treating acute post-surgical pain,27 they produce a high incidence of drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, and constipation compared to NSAID analgesics.25,28 Only one patient (4%) in this study reported an opioid-like side effect (constipation).

The major weakness of this study was its open-label design, and it lacked a placebo control and an active comparator drug. The study was also not powered to determine differences between the sites of implant placement and the number of implants placed.

Conclusion

The newest formulation of ketorolac, an intranasal formulation, is available in a disposable, multi-dose, metered spray device that allows patients to self-administer the drug outside of the hospital setting. Whether intranasal ketorolac offers advantages in onset or peak effects over other FDA-approved oral and less costly NSAIDs in treating postsurgical dental implant pain can only be verified with well-designed clinical trials.

DISCLOSURE

This study was supported by a grant from Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Shirley, New York. Dr. Hersh was a recipient of the grant from Luitpold Pharmaceuticals that funded this study, and he and Dr. Bockow each received travel grants from Luitpold Pharmaceuticals to present some of this data at the Academy of Osseointegration 2013 Annual Meeting. Mr. Hutcheson was a paid consultant for this study.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Rebecca Bockow, DDS, MS

Resident in orthodontics and periodontics, Departments of Orthodontics and Periodontics, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Jonathan Korostoff, DMD, PhD

Associate Professor of Periodontics, Director of the Master of Science in Oral Biology Program, Department of Periodontics, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Andres Pinto, DMD, MPH

Associate Professor of Oral Medicine and Community Oral Health, Director of Oral Medicine Services and Chief, Division of Community Oral Health, Department of Oral Medicine, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Matthew Hutcheson, MS

Adjunct Professor, Departments of Education, Widener University, Chester, Pennsylvania, and Delaware Valley College, Doylestown, Pennsylvania; Partner, Tegra Analytics, Doylestown, Pennsylvania

Stacey A. Secreto, CRC

Clinical Research Coordinator, Department of Oral Surgery and Pharmacology, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Laura Bodner, DMD

Resident, Department of Orthodontics, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Elliot V. Hersh, DMD, MS, PhD

Director, Division of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Professor, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Pharmacology, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

REFERENCES

1. Zarb GA. Introduction to osseointegration in clinical dentistry. J Prosthet Dent. 1983;49(6):824.

2. Schmitt A, Zarb GA. The longitudinal clinical effectiveness of osseointegrated dental implants for single-tooth replacement. Int J Prosthodont. 1993;6(2):197-202.

3. Zarb GA, Schmitt A. The longitudinal clinical effectiveness of osseointegrated dental implants in posterior partially edentulous patients. Int J Prosthodont. 1993;6(2):189-196.

4. Zarb GA, Schmitt A. The longitudinal clinical effectiveness of osseointegrated dental implants in anterior partially edentulous patients. Int J Prosthodont. 1993;6(2):180-188.

5. American Academy of Implant Dentistry website. http://www.aaid-implant.org/about/Press_Room/Dental_Implants_FAQ.html. Accessed Aug 11, 2012.

6. American Dental Association website. 2007 Survey on Surgical Dental Implants, Amalgam Restorations, and Sedation. http://www.ada.org/1443.aspx. Accessed August 10, 2012.

7. Al-Khabbaz AK, Griffin TJ, Al-Shammari KF. Assessment of pain associated with surgical placement of dental implants. J Periodontol. 2007;78(2):239-246.

8. Karabuda ZC, Bolukbasi N, Aral A, et al. Comparison of analgesic and anti-inflammatory efficacy of selective and non-selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in dental implant surgery. J Periodontol. 2007;78(12):2284-2288.

9. Biron RT, Hersh EV, Barber HD, Seckinger RJ. A pilot investigation: post-surgical analgesic consumption by dental implant patients. Dentistry. 1996;16(3):12-13.

10. Bölükbasi N, Ersanli S, Basegmez C, et al. Efficacy of quick-release lornoxicam versus placebo for acute pain management after dental implant surgery: a randomised placebo-controlled triple-blind trial. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2012;5(2):165-173.

11. González-Santana H, Peñarrocha-Diago M, Guarinos-Carbó J, Balaguer-Martínez J. Pain and inflammation in 41 patients following the placement of 131 dental implants. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10(3):258-263.

12. Hashem AA, Claffey NM, O’Connell B. Pain and anxiety following the placement of dental implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2006;21(6):943-950.

13. Grant GM, Mehlisch DR. Intranasal ketorolac for pain secondary to third molar impaction surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(5):1025-1031.

14. Bacon R, Newman S, Rankin L, et al. Pulmonary and nasal deposition of ketorolac tromethamine solution (SPRIX) following intranasal administration. Int J Pharm. 2012;431(1-2):39-44.

15. Boyer KC, McDonald P, Zoetis T. A novel formulation of ketorolac tromethamine for intranasal administration: preclinical safety evaluation. Int J Toxicol. 2010;29(5):467-478.

16. SPRIX (ketorolac tromethamine) Nasal Spray [package insert]. Shirley, NY: Regency Therapeutics; 2011.

17. Singla N, Singla S, Minkowitz HS, et al. Intranasal ketorolac for acute postoperative pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(8):1915-1923.

18. Moodie JE, Brown CR, Bisley EJ, et al. The safety and analgesic efficacy of intranasal ketorolac in patients with postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(6):2025-2031.

19. Brown C, Moodie J, Bisley E, Bynum L. Intranasal ketorolac for postoperative pain: a phase 3, double-blind, randomized study. Pain Med. 2009;10(6):1106-1114.

20. McAleer SD, Majid O, Venables E, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of ketorolac following single intranasal and intramuscular administration in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47(1)13-18.

21. Hersh EV, Levin LM, Cooper SA, et al. Ibuprofen liquigel in oral surgery pain. Clin Ther. 2000;22(11):1306-1318.

22. Breivik EK, Barkvoll P, Skovlund E. Combining diclofenac with acetaminophen or acetaminophen-codeine after oral surgery: a randomized, double-blind single-dose study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;66(6):625-635.

23. Mehlisch DR, Aspley S, Daniels SE, Bandy DP. Comparison of the analgesic efficacy of concurrent ibuprofen and paracetamol with ibuprofen or paracetamol alone in the management of moderate to severe acute postoperative dental pain in adolescents and adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, single-dose, two-center, modified factorial study. Clin Ther. 2010;32(5):882-895.

24. Turner CL, Eggleston GW, Lunos S, et al. Sniffing out endodontic pain: use of an intranasal analgesic in a randomized clinical trial. J Endod. 2011;37(4):439-444.

25. Hersh EV, Kane WT, O’Neil MG, et al. Prescribing recommendations for the treatment of acute pain in dentistry. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2011;32(3):22-30.

26. TORADOL (ketorolac tromethamine) tablet, film coated [package insert]. San Francisco, CA: Genentech Inc. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=c0336606-7366-41ce-9cef-aa6524b92b11. Accessed August 24, 2012.

27. Hersh EV, Pinto A, Moore PA. Adverse drug interactions involving common prescription and over-the-counter analgesic agents. Clin Ther. 2007;29(suppl):2477-2497.

28. Cooper SA, Precheur H, Rauch D, et al. Evaluation of oxycodone and acetaminophen in treatment of postoperative dental pain. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;50(6):496-501.

Related Content: A CE article, Opioid Prescribing in Dentistry, is available at dentalaegis.com/go/cced453